In 2013 and 2014, Prime Minister Abe’s cabinet put in place a ‘growth strategy’ based in part upon a white paper that I had led in 2010.

The core theme in both was that the enhancement of productivity and profitability of corporations was essential for Japan’s future, and the central ‘pillar’ of the growth strategy was to improve corporate governance. A stewardship code and corporate governance code[1] were put in place, and other reforms followed.

Progress is slowing

So far, so good. On the one hand, enough of a base of ‘best practice’ concepts and new mindsets now exists that if shareholders ask for specifics, more and more Japanese companies will heed their reasonable requests. As I wrote a year ago, at this point the pace of change is mainly up to investors.

But in a country where many modern corporate governance practices were avoided for 40 years, change does not come easily. Many institutional investors are still getting their engagement ‘legs’. They do not know what is changing on Japanese boards and what is not, what exactly to ask companies for, and how to get it.

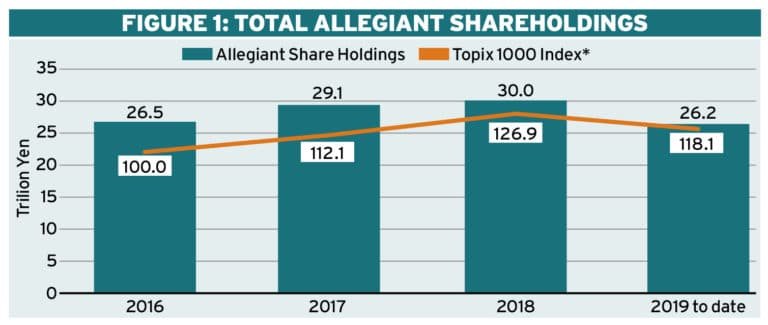

At the same time, many companies are resisting change or just sliding by with superficial motions, and their defensive ‘wall’ of cross-shareholders and other yes-man ‘allegiant holders’ remains high – or has even increased in size. On average for non-financials in the TSE First Section, more than 55 per cent of net assets is stuck in non-core holdings and cash. Unsurprisingly, in 2018, for a variety of reasons the Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA) ranked Japan seventh out of 12 countries in Asia in its overall CG rankings[2] (see Figure 1, below).

Reform is losing steam

Thus, is it essential that the Tokyo Stock Exchange (JPX/TSE) and the various regulatory agencies keep up reform momentum. However, one senses a desire from these groups to ‘declare victory’, and they have a tendency to not fully coordinate with each other. If Prime Minister Abe’s cabinet did more to make the key players coordinate their efforts in key areas, meaningful governance change (and protection of investors) would accelerate.

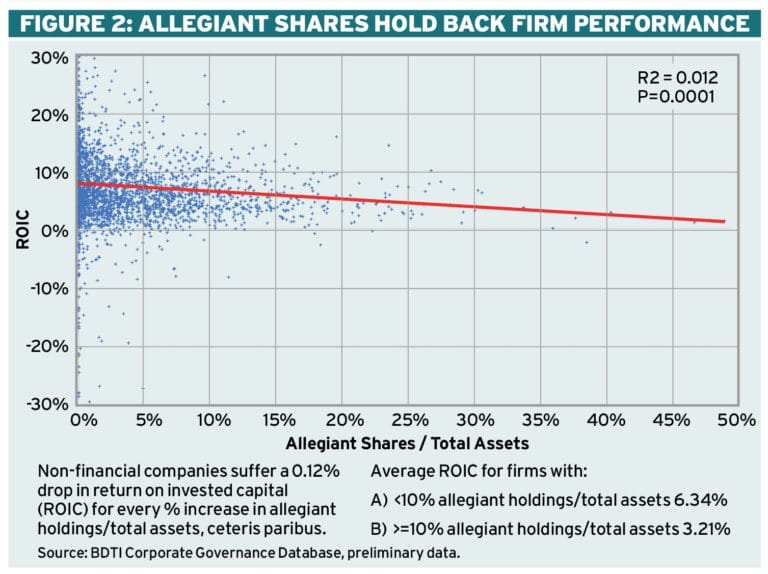

Japan’s goal should not be to come close to, or equal, other major markets. It should be to exceed the quality and trustworthiness of other major markets. As the most developed economy and largest stock market in Asia, it has the potential to do this. Prime Minister Abe has pledged to ‘continue to advance corporate governance reforms in line with global standards, including appointment of external directors and disclosure of officer remuneration’.[3]Now is the time for him to realise that vision (see Figure 2, above).

The unfinished business

1. Detailed rules for an independent committee

Despite its numerous exhortations to ‘fully utilise’ independent directors, Japan’s Corporate Governance Code (CGC) still doesn’t set forth clear and consistent rules for a fully independent ‘nomination and compensation committee’, the one place where their independence could be best leveraged to improve governance.

Obviously, a minority of three independent directors on a 10-person board will have limited sway. But if appointed to a committee, they can control the most important levers of governance where independence is essential. In fact, it was precisely in order to subsequently require such a committee, that I insisted on ‘multiple’ independent directors when I first proposed the key items that I thought should be in the CGC.

The next revision of the CGC should set forth clear requirements and best practices for such a committee. It should also require the independent committee to advise the board not only on nominations and compensation matters, but also on any other matter with respect to which more than two directors or a related party may have an inherent conflict of interest or special interest, in the opinion of a majority of the independent directors.

2. A clear requirement for a majority of independent directors on the board

A separate principle, clearly requiring a majority of independent directors, needs to be set forth in the CGC, regardless of the presence of such a committee. Otherwise, one cannot have full confidence that the selection of directors or committee members will be made on an objective and neutral basis.

By global standards, the CGC only encourages a choice between (a) a half a loaf: a majority of independent directors, but no committees are required, and (b) a weak and vague loaf: a nomination or compensation committee that has ‘substantial participation’ by independent directors on it, but is chosen by a board dominated by executive directors, and the chair of which may be an executive director (even the CEO). The loose wording of this section would not pass muster in most other developed nations.

3. Codifying the role and responsibilities of executive officers

Japan has to deal with an impending problem that the Governance Code itself has created, by amending the Company Law so as to create legally valid ‘executive officer’ (shikko yaku) roles at all Japanese public companies. This is an area that shows that not everything can be handled by ‘soft law’ (non-mandatory principles, such as the CGC), and that some issues can only be addressed by changing the Company Law (the ‘hard law’) itself.[4]

In the two legally permitted governance structures that are utilised by 99 per cent of Japanese companies, the more independent directors are added to a board, the smaller becomes the number of directors who can be appointed as legally valid ‘executive directors’, and in particular, are eligible to be appointed as the CEO at any time. Thus, the positive trend to appoint more independent directors is at the same time creating a situation where the pool of persons who can be considered as a replacement CEO when one is quickly needed is becoming smaller and smaller.

This is not a healthy situation, especially since the CGC itself appropriately stresses the importance of a timely process for replacing the CEO when and if necessary. To make matters worse, at these companies (99 per cent of listed companies), persons who are non-director ‘officers’ not only cannot be appointed to serve as CEO without an AGM, but also carry no fiduciary duties and therefore cannot be sued by shareholders for violation of duties of due care, reporting and the like.

Thus, now there is not only less ability to flexibly select the most senior executives, but also less legal accountability for executives overall.

4. Consolidation of overlapping disclosure reports

As ACGA and many others have pointed out, Japan needs to consolidate its myriad disclosure reports so that they are much more convenient to use. This will require strong political leadership from the top, because it can only be done by abandoning the separate bureaucratic silos of Ministry of Justice (MOJ), Financial Services Agency (FSA) and TSE/JPX-required disclosure.

Japan needs to integrate financial reports, business reports, and governance disclosure into a single document (the yuho, or annual financial report, submitted to the FSA). Next, it needs to require this document to be published prior to the AGM so that information can be used by shareholders on a timely basis.

To give just one example of the problem, currently less than one per cent of Japanese public companies release their annual financial reports, which contain all disclosure required by securities law, before the AGM has been held. Investors also need to keep in mind that business reports in the proxy statement, ‘kessan tanshin’ earnings reports, and JPX/TSE corporate governance reports are not subject to potential liability under securities law in case of misrepresentations or material inaccuracies. This is the major reason there is so much sloppy, vague and meaningless disclosure language in TSE/JPX governance reports: they entail no legal liability.

Notably, the proliferation of so many different disclosure reports, and the burdens that imposes on investors, was a principal reason why the ACGA lowered Japan’s corporate governance rating in its 2018 report. FSA, MOJ and the Minisry of Economic Trade and Industry (METI) have had initial discussions on the concept of combining different reports, but progress is very slow.

5. Protection of minority shareholder rights

To come closer to the global standard that the Prime Minister has promised, Japan will need to address the protection of minority shareholder rights and ‘fairness’ in M&A transactions not only by means of non-compulsory METI ‘guidelines’, but also by amending the Company Law (the hard law) and compulsory stock exchange listing standards.

As things stand now, not only a 51 per cent parent company but a holder of merely 25 per cent or so can do all sorts of things to destroy value that should accrue to minority holders, whether it be by pushing through unnecessary dilutive capital increases, stopping takeover bids or beneficial merger proposals in their tracks, self-servingly pushing through their own underpriced deals, or ‘tunneling’ of all sorts, including simply requiring excess cash to be deposited with the large holder rather than paid back to shareholders.

This is an area where so much has not been done yet that listing everything would require another article. Therefore, I will only mention the two policy changes that I think would help the most. First, the JPX/TSE listing standards should require shareholder approval for capital increases that dilute shareholdings by more than 20 per cent. Second, in the case where a shareholder sues a director who voted for a transaction affecting ownership or capital structure or involving a related party, the Company Law should reverse the burden of proof unless the board had obtained the advance approval of the fully independent committee mentioned earlier in this article.

Here again, only strong political leadership can bring about the coordination between different agencies and the stock exchange that is needed.[5]

6. Enhancing transparency to reduce entrenchment and enhance inclusiveness

Japan is viewed by global investors as one of the markets that has the most to gain from greater diversity and inclusiveness at all levels in many companies, and the reduction of ‘old boy networks’ and other practices that tend to lead to entrenchment of management.

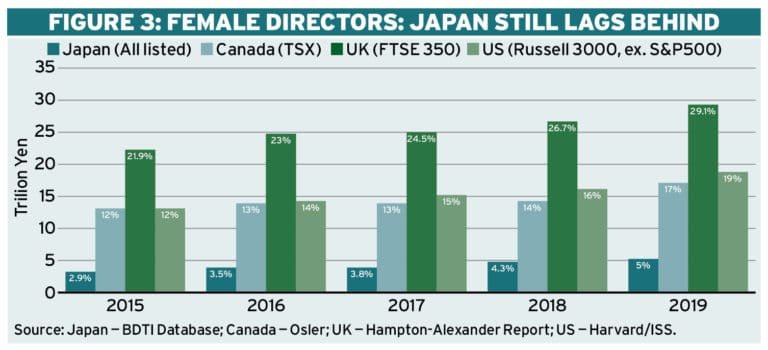

Here, I am referring not only to the need to appoint more female directors and managers (see Figure 3, above). Rather, many Japanese companies need to promote diverse thinking in general, by appointing more foreigners and facilitating market pressure (via transparency) to abandon outdated practices that perpetuate narrow-mindedness and stymie creativity and dynamism.

The benefits of diversity do not come from merely increasing the number of women on corporate boards. They arise from changing corporate ingrown cultures so that different opinions and perspectives are more easily tolerated and even encouraged, management innovation can more easily occur, and practices and allegiances of the past are quickly abandoned when they are no longer effective.

Japan should require disclosure of the number of women and foreigners (a) on the boards and (b) among the executive ranks from the middle level upwards. In addition, if directors (CEO or otherwise) are hired as ‘advisors’ (soudanyaku or komon) after their retirement from the board, their compensation amount and general job responsibilities should also be disclosed in the yuho financial report[6].

7. Strengthening stewardship throughout the investment chain

Japan’s Stewardship Code (SC), which is a completely voluntary code but is successful in the sense that most asset management fiduciaries in Japan have signed it, needs to be strengthened in the following important respects: (a) clear rules are needed to countenance collective engagement as long as the collective action is unconditionally ‘opt out’ in nature, and these rules must apply even in the case of ‘making recommendations’ to companies; (b) public disclosure of per-item votes should not be voluntary (but rather, mandatory) if an institution has signed the Code; and (c) the FSA should create a system to standardise the format of such per-item vote disclosures and make them freely available to investors in fully machine-readable format.[7]

At the same time, as the regulator of corporate pension funds, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) should not stop at meekly ‘encouraging’ corporate pension funds to sign the SC, but should take more meaningful steps to serve the interests of the pensioners it is charged with protecting. Specifically, it should require corporate pension funds to include a description of their policy towards ‘stewardship’ in their formal investment policies, and should require them to disclose to employees and pensioners whether their pension fund has signed the SC or not.[8]

So far, only eight defined-benefit pension funds of non-financial companies have signed the SC, out of a total universe numbering more than 700 funds. It is clear that neither MHLW, corporate pensions, nor their corporate sponsors are very serious about stewardship, even though Japanese companies pride themselves on the strength of their covenant to employees. Yet, asset owners such as corporate pension funds are one of the most important players in the investment chain, because they decide which asset managers are awarded mandates (or not), the amount of funds allocated to them, and the proxy voting and other stewardship practices that are required of them.

Here again, strong political leadership is essential. Sound familiar?

Footnotes:

Opinions are my own.

1.I myself was lucky enough to get the governance code ball rolling, by proposing it to key lawmakers and making a presentation to the committee in charge.

2.Asian Corporate Governance Association, CG Watch 2018

3.Policy Speech by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe to the 198th Session of the Diet, January 28, 2019, https://japan.kantei.go.jp/98_abe/statement/201801/_00003.html.

4.Last year, I was able to convince METI of the need to do this, and METI formally suggested amendment of the law to the Ministry of Justice. However, the MOJ council ignored this suggestion, showing that political leadership is needed. See the link below (Japanese only): http://www.moj.go.jp/content/001237422.pdf.

5.Regarding protection of minority shareholder rights, see my public comment submission to METI. https://bdti.or.jp/en/blog/en/metipubcomnb/.

6.Regarding advisors, as background see: https://bdti.or.jp/en/blog/en/advisorg/.

7.See: The Unfinished Business of Japan’s Stewardship Code, https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8D79PTM.

8.This is what I proposed in 2018, which was not put in place but led to an inter-agency study group, the new CG Code principle on stewardship, and a MHLW web page to encourage pension funds. See article: https://www.top1000funds.com/2019/04/japans-governance-conundrum/. See also: https://bdti.or.jp/en/blog/en/ishinoueni3nen/.