Directors and C-suite executives have never been as powerful as they are in today’s global market. The scope and wealth of the world’s 100 largest listed companies – with an estimated combined market capitalisation of more than $15 trillion[1] – rivals that of many countries’ GDP. Whether, how and to what extent these leaders decide to make good use of this power is a key challenge for us all. Each time they choose to steer their companies toward integrity, they increase their company’s potential to have a positive impact on our markets, governments, societies and our environment.

It’s easy to lose sight of that, however. Whether by error, neglect or by actively choosing to engage in reckless risk-taking, corporate scandals continue to make headlines. When the OECD conducted its autopsy of the financial crisis, we found that, in many cases, enterprises did not take a firm-wide approach to risk and risk management was considered non-essential to a firm’s business strategy.[2] Risk managers were often separated from management and not regarded as an essential part of implementing the company strategy and, in many cases, enterprises did not take a firm-wide approach to risks facing the company.

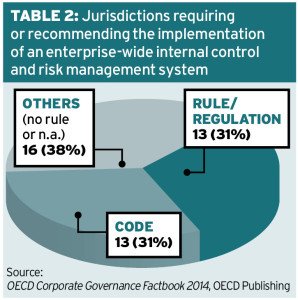

It would be misleading and irresponsible not to credit all of the governments, companies and boards who have made huge strides since the crisis. This includes ensuring that boards more adequately address risk, including compliance risks related to, for instance, bribery, anti-competitive business practices or violation of labour standards and human rights. Today, most jurisdictions require that the board assume responsibility for risk management. According to a recent survey of corporate governance practices in 42 jurisdictions, more than half set out board responsibilities with respect to risk management either in law or regulations (26 per cent) or in codes (33 per cent).[3] Almost two-thirds of jurisdictions require or recommend the implementation of an enterprise-wide internal control and risk management system (beyond ensuring the integrity of financial reporting) – see Table One and Table Two.

Despite this progress, there remains a gap between what business leaders embrace as their corporate commitments and the reality of their actions.

There is a disconnect between how many companies make business decisions, often with the best intentions, and how those decisions are linked to decisions taken to ensure compliance and responsible risk management. A 2014 PwC survey on the state of compliance,[4] for example, indicates that even in the companies that have taken the important step of establishing a compliance committee, only a fraction include representatives with connections to the company’s business units (such as business operations or sales and marketing).

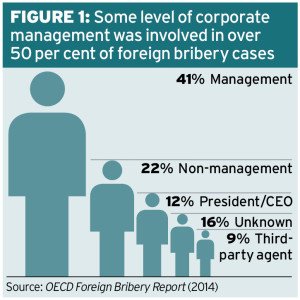

A parallel EY survey[5] from the same year indicates that there has been a reduction in the level of reporting on compliance issues to boards. It also showed that six per cent of survey respondents, including C-suite executives, are willing to justify unethical behaviour, such as misstating company financial performance. These findings jibe with the findings of the 2014 OECD Foreign Bribery Report,[6]which shows that 53 per cent of the 400-plus foreign bribery cases included in the report took place with the involvement of some level of corporate management or even the CEO – see Figure One.

And then there are the enforcement statistics: of the world’s 50 largest corporate penalties imposed since 1990, 42 per cent of all cases and 64 per cent of all fines were imposed only in the last two years.[7] Six of the 41 companies on the list appear more than once; one appears four times. Not only are these fines painful for the companies involved, but non-compliant companies increase the cost of compliance for those that are trying to play by the rules – for example, by creating a necessity for stricter or more vigilant regulations and/or enforcement, loss in market and investor confidence, more limited access to finance, etc.

And then there are the enforcement statistics: of the world’s 50 largest corporate penalties imposed since 1990, 42 per cent of all cases and 64 per cent of all fines were imposed only in the last two years.[7] Six of the 41 companies on the list appear more than once; one appears four times. Not only are these fines painful for the companies involved, but non-compliant companies increase the cost of compliance for those that are trying to play by the rules – for example, by creating a necessity for stricter or more vigilant regulations and/or enforcement, loss in market and investor confidence, more limited access to finance, etc.

All this begs the question to which we at the OECD are trying to respond, “What is the missing piece of the puzzle?”. There is no shortage of laws, rules, principles, guidelines or advice for companies. And, all relevant actors claim to be on the same page as to what is needed in order to pursue business interests responsibly and with integrity. We believe that the nexus between compliance and corporate governance is the key to bridging this implementation gap.

The OECD Principles of Corporate Governance, currently under revision to align them more closely with the corporate governance practices that have evolved over the decade since their adoption, remain the internationally recognised standard in this field. The OECD Principles focus on the responsibilities of the board. These responsibilities include setting the ethical tone of the company and being satisfied that its compliance system is fundamentally sound. For boards that take these responsibilities to heart, what does this mean in practice?

When answering that question, it is easy to agree with broad statements about corporate misconduct (it’s bad), the role of the board (it’s important) and links to a corporation’s compliance and risk management functions (they should be there). It is harder to know what this means for boards and the companies they oversee (beyond hard work and long-term dedication). We have, therefore, decided to focus our efforts to help companies implement this chapter of the Principles. We hope that this will enable us to better understand why some companies fail to prevent corporate misconduct and find practical ways to build effective compliance into corporate governance.

We will be happy to report on these efforts in the coming months. Any Ethical Boardroom readers who would like to engage with the OECD on this issue are invited to visit OECD to find ways to get involved.

FOOTNOTES 1 PwC, Global Top 100 Companies by market capitalisation, 31 March 2014 update, available at http://press.pwc.com/global/global-market-capitalisation-tracker-shows-us-businesses-eclipsing-the-rest-of-the-world/s/4466f468-3015-4c41-8399-8df4ec88eb42 2 OECD (2014), Risk Management and Corporate Governance, Corporate Governance, OECD Publishing, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264208636-en 3 OECD Corporate Governance Factbook: 2014, OECD Publishing available at www.oecd.org/daf/ca/corporate-governance-factbook.htm, with information updated until December 2014. The survey of measures for ensuring governance of internal control and risk management referenced here included the 34 OECD Members plus Argentina; Brazil; Hong Kong, China; India; Indonesia; Lithuania; Saudi Arabia; and Singapore. 4 2014 PwC State of Compliance Survey available at www.pwc.com/us/stateofcompliance 5 2014 EY 13th Global Fraud Survey available at www.ey.com/GL/en/Services/Assurance/Fraud-Investigation—Dispute-Services/EY-reinforcing-the-commitment-to-ethical-growth 6 OECD (2014), OECD Foreign Bribery Report: An Analysis of the Crime of Bribery of Foreign Public Officials, OECD Publishing, Paris, available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/ 9789264226616-en 7 See Global Investigation Review’s annually updated Enforcement Scorecard, available at http://globalinvestigationsreview.com/enforcement-scorecard