Latin America is often treated as a homogeneous region with a common language, history or culture, but in fact it is a very diverse realm. While it would be futile to attempt a rigorous description of ‘Latin American Board Practices’, we can take a modest ‘10,000 feet view’ to describe the broader issues affecting the corporate governance in the region.

Listed corporations in Latin America, with very rare exceptions, are largely dominated by the figure of a controlling shareholder (CS). They are either family-controlled business groups, multinational corporations or the State. Besides preferred series, these CSs own in fact more than 50 per cent of the common stock. Even figures of 70 per cent or 80 per cent are not rare.

Board composition and processes are largely a direct reflection of this ownership structure. The ‘disciplining’ threat of a hostile takeover is just science fiction here.

The majority of the board is elected by the CS, including family members, executives of the business group or, in the case of State controlled firms, government officers or political figures of the ruling parties. These boards, typically 9-11 members in size, will also have one or two directors voted by minority shareholders. Chairman of the board will generally be appointed directly by the CS (if not appointing him/herself).

In general, chairman and CEO will be two distinct individuals. In fact, in many countries of the region, the law prohibits CEOs to be members of the board. Here the hire/fire and compensation of CEOs will almost invariably be at the discretion of the controlling shareholder. The latter will usually get involved in the most important management decisions and secure a perfect alignment with the CEO and his/her team. The theoretical agent-owner challenges of other latitudes will not apply here.

Constrained growth

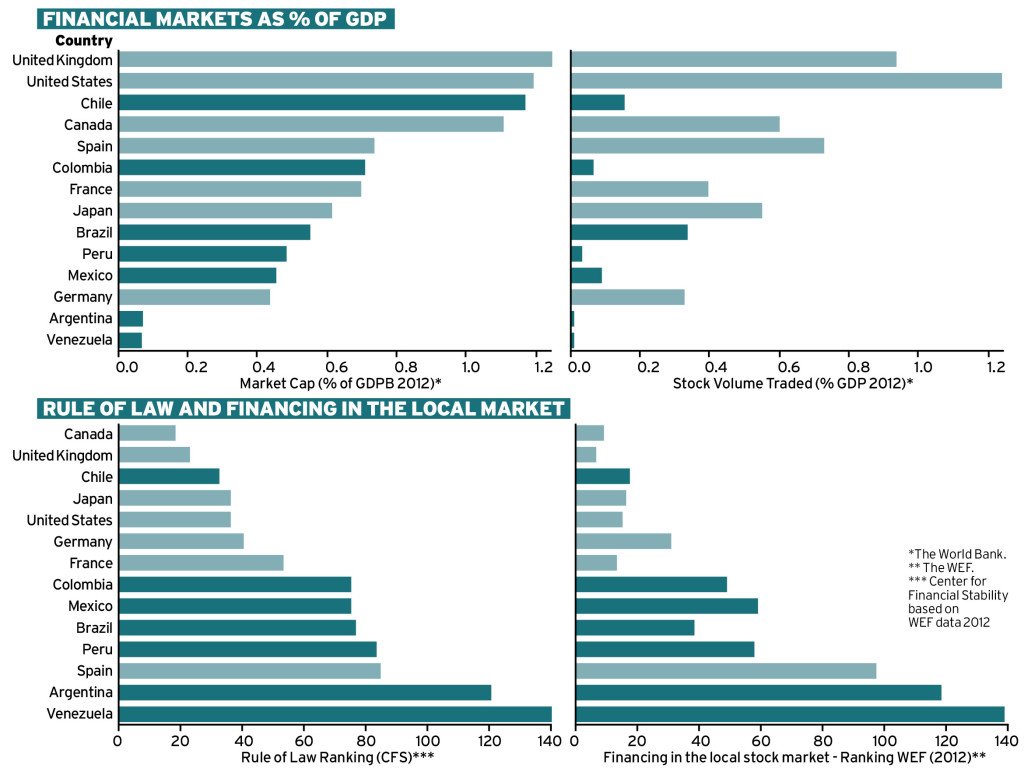

Even after a decade of remarkable economic growth, financial markets in Latin America are still less developed than those in most modern economies, especially when compared with English speaking countries. Fewer firms seek resources in the equity markets, constraining their growth opportunities.

In addition, traded volumes are relatively shallow, also due to the fact that floating stocks released from the hands of controlling shareholders are relatively scarce. This circumstance creates enormous mobility barriers for large investors. Voting ‘with their feet’ on the quality of corporate governance practices of a given firm is not always possible. The lack of depth also makes it easier and cheaper to manipulate prices than in most-developed equity markets. Accordingly, concepts such as fair price, supply and demand are not always well reflected in the implicit market valuation of companies

At a global level, the strength of institutions and the rule of law are closely related with the development of financial markets. In this sense, Latin America is at a historical disadvantage.

The famous statement “For my friends whatever they want; for my enemies, the law”, attributed to Brazilian dictator Getulio Vargas, is often quoted as a way to illustrate the use and abuse of the law and the degree of institutional underdevelopment in the region. Accordingly, misbehaviour and expropriatory attempts by a CS will be harder to discipline. Even in the unlikely scenario of legal sanctions, they will usually be mild and take a very long time to be settled in courts.

Winds of change

The historic context has long imposed two important challenges for minority shareholders and regulators: the lack of ‘distance’ between management and governance and the subversion of minority interests to those of the controlling shareholder. Yet, a number of factors are challenging the status quo and winds of change are gusting (see table below).

An extremely significant change in the region was initiated by the pension system reform promoted in Chile in 1981 and later extended to other countries in the region. Today, through private pension administrators, called the AFPs, ninety million people are shareholders and creditors of the companies in the region. Their individual savings, amounting to approximately five hundred billion dollars, tilt the debt and equity markets. Their vote is a massive political power affecting the press, regulators and legislatures in significant ways. In fact, it is more and more common that they succeed in blocking questionable transactions that would have passed just a few years ago.

Stronger and more active regulators

In the last decade a plethora of market failures has captured public attention in Latin America. Related party transactions, accounting fraud and sheer poor board performance provided the tipping point to boost corporate regulation reform. Accordingly, just about every country in the region has increased the number and quality of regulators’ teams, provided with more resources and, what is more important, with the instruments to control and penalise those in default.

The frequency and amounts involved in penalties have put managers, board members and the press on alert. Just as an example, a few weeks ago the Chilean equivalent of the SEC imposed a $164 million fine in a case of related-party transaction. This set an historic record and a call for attention to controlling shareholders and board members.

Besides the normal competitive forces, the more active role of regulators and institutional investors have forced board members to get out of their laid-back positions.

Norms have imposed the concept that audit committees should also be accountable to review potential related party transactions and protect minority interests. This is reinforced by the fact that these committees are usually composed and chaired by minority appointed directors. Perceived or real higher liabilities have also pushed directors to devote more time, energy and methodology into risk management and compliance activities.

Professionalisation of board members

Not too long ago the ticket to join a corporate board was the personal relationship with a controlling shareholder. Today filling a board seat normally involves a headhunting firm. Board education has also thrived. Training programs and corporate governance centres have developed in every country in the region. Even some local directors are voluntarily getting certification from foreign entities, such as the UK’s Institute of Directors.

Today, the stocks of many of the largest corporations in the region are traded in developed markets, such as the New York Stock Exchange. This has brought practices such as compensation and governance committees and Directors and Officers Liability Insurance.

Market integration is also operating at a regional level. Chile, Peru, Colombia and Mexico stock exchanges are working to create a fully integrated market (known as MILA). Regulators, stock exchanges and institutional investors are working together in an effort to impose higher governance standards and make regulation converge much faster than before.

In summary, board practices in the region are converging to those of the rest of the world, and it is happening very fast. Nevertheless, it is very important to acknowledge the historical context of ownership structure and institutional development to avoid costly mistakes. Foreign plug-and-play regulations or practices will not necessarily make sense in Latin America.