US Navy Admiral Harry Harris, until recently the commander of the United States Pacific Command and now the US Ambassador to South Korea, has described the geographical expanse and cultural spread across Asia as ‘from Bollywood to Hollywood, from polar bears to penguins’.[1]

It’s an apt description for the region’s cultural, economic, linguistic and geopolitical diversity – and for the breadth of Asian financial markets, which are each differentiated by regulation, currency, investor base and valuation.

Across Asia, minority shareholders have found a voice to engage management and each other. Activists, though tempted by the low valuations and suboptimal balance sheets, have long avoided Asia due to poor corporate governance, insider boards, family- or group-controlled shareholder structures, frequent corporate scandals and a lack of transparency.

Today, those same issues are now considered points of entry in engagements to increase shareholder value. Further, the welcome mat has been laid out for activists by regulatory bodies across Asia, which are clearly trying to harness shareholders to help drive more productivity at companies and on companies’ assets, which would drive growth for their economies as a whole.

As a result, activism, long a successful US strategy, has now come to Asia in a meaningful way. Engagements have increased from a total of 10 back in 2011 and only 49 in 2014, to 106 last year.[2] Activism in Asia is off to a strong start in 2018, with the number of campaigns launched during the first quarter in line with those initiated during the same time in 2017.[3] But, as Admiral Harris understood, Asia is a big, diverse place, so it’s useful to break down the developments and opportunities, country by country.

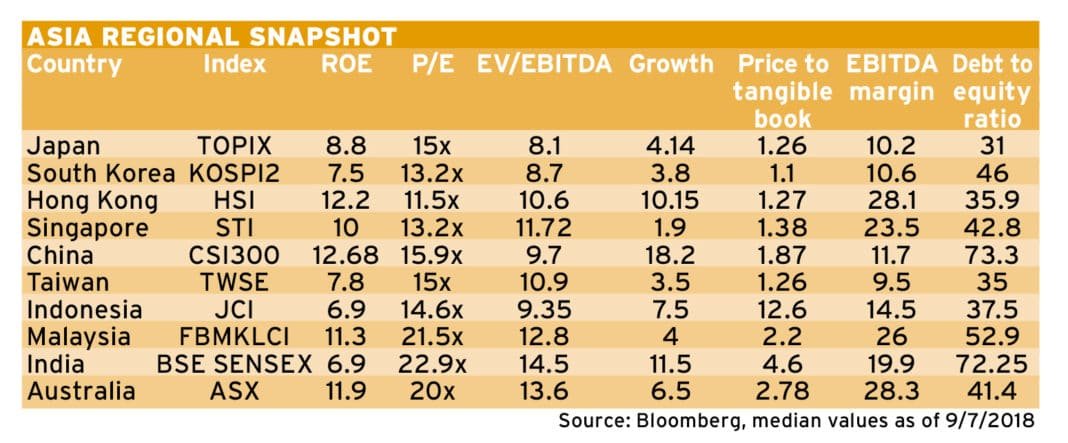

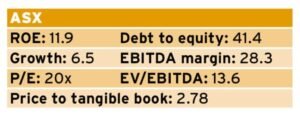

Interestingly, the level of activist activity across the region does not seem to be dictated by the comparative strength of a country’s general standard of corporate governance, per se, but rather by the net value that companies’ management teams are adding for shareholders (which might itself be the most important component of corporate governance). That value is frequently reflected in the multiples that investors have been prepared to invest in the various markets. Often where returns on equity, margins and growth are low, minority shareholders have felt the need to be more vocal in engaging with management to increase the company’s value. When growth and margins are high, often when the founder is running the company, there has been less interest (and need) by shareholders to engage publicly (see Asia Regional Snapshot, below).

Japan: cheap for a reason

It’s one of the cheapest of global equity markets with more than 39 per cent of companies in the Topix trading below tangible book value. But Japan is cheap for a reason. And that reason is a lack of corporate governance in the form of failure by management teams to increase ROEs and shareholder returns (among other metrics). With the welcoming of government, activists have dramatically increased their activity in an effort to unlock that value.

It’s one of the cheapest of global equity markets with more than 39 per cent of companies in the Topix trading below tangible book value. But Japan is cheap for a reason. And that reason is a lack of corporate governance in the form of failure by management teams to increase ROEs and shareholder returns (among other metrics). With the welcoming of government, activists have dramatically increased their activity in an effort to unlock that value.

Developments in corporate governance: One rule of thumb we have found as foreign investors in Japan is no conversation about activism can take place without mention of Steel Partners the last time activists engaged in Japan back in the mid-2000’s.

So, let’s begin there. Steel Partners’ Warren Liechtenstein came to Japan with money and an attitude of pure, Western-style capitalism. He targeted numerous companies, the most famous of which was Bull-Dog Sauce. Bull-Dog is a listed company that sells a distinctive and much-beloved intense Worcestershire sauce in Japan (think Coleman’s mustard in the UK or Heinz ketchup in America). But for Warren, Bull-Dog’s more distinctive features were the price of its shares, which implied a negative equity value and management’s complacency regarding the share price. The problem was, he was prepared to tell anyone that. On a visit to meet Bull-Dog’s management in Tokyo, he said he planned to ‘educate’ and ‘enlighten’ Japanese managers about American-style capitalism.[4]

As a result, when the company enacteda poison pill, he was deemed by the court

to be a hostile acquirer. (Relatedly, in 2007, national broadcaster NHK began running a drama series called Vulture about a Japanese fund manager who acquires indebted companies for a US investment firm. Its tagline: ‘Is that man the devil or a saviour?’)

The fun (and profitable) part for Steel Partners and its investors is that while he did not manage to achieve a takeover at Bull-Dog, he cashed out of three-quarters of his shares at the same price of shares everyone else got equity at, so he did, presumably, make money. Nevertheless, he remains the paradigm of the ‘abusive acquirer’ and foreign vulture investor in Japan and the lower court ultimately ruled against Steel Partners (despite the language being toned back by the Upper Court). It was seen as a sign by foreign investors that Japan was shut to activist shareholder engagement – until the advent of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s ‘Abenomics’ in 2012.

Opportunities: Today, with Abenomics in its sixth year and Japan’s ROE revolution in its fourth year, along with the newly revised Corporate Governance Code (2018) and the revised Stewardship Code (2017), we are in very different times. Votes against management have been steadily increasing over the past four years and the opposition rate – defined as the number of proxy proposals on average voted against by all investors – is now at 3.4 per cent, up from 2.6 per cent in 2015 [5]

Engaging with companies successfully and, if necessary, staging a proxy vote requires engaging with the entire shareholder base. While the percentage ownership by shareholder type varies by company, shareholders in Japan can broadly be categorised as:

- Foreign shareholders

- Corporates subject to the Corporate Governance Code

- Domestic asset managers and pensions funds subject to the Stewardship Code

- Retail investors

Three out of four of these shareholder types have begun voting more aggressively in their own economic interests. The exception is corporate holders. As an investor in Japan, we see an increasing number of domestic asset managers voting in line with their stewardship duties and against management. But corporate shareholders, subject to the newly revised Corporate Governance Code, should be voting in the best interest of the company’s underlying value. Instead, they continue to look for excuses and work-arounds so as to not abide by the spirit of the Code.

We believe the problem of a lack of adherence to the spirit of the Code has solutions. The government continues to encourage the unwinding of cross-shareholdings. Calling out these corporate holders that vote against proxies that are clearly in their economic interests and in line with the Code can make it more painful for them to act against their own duties of care and loyalty to their company instead of participating in a management mutual protection pact.

As a result of the newly friendly environment for corporate engagement, shareholders of all stripes have come to Japan to engage. These range from managers that specialise in friendly-only suggestivism (‘free consulting services’), to those, like us at Oasis, that span the spectrum from friendly to increasingly activist approaches, to those that are almost exclusively hostile to management. All of these approaches have had their share of successes recently.

I believe the continued success of engagements in Japan in terms of shareholder-friendly company improvements and subsequent share price appreciation will beget further success. The flurry of poison pills that were adopted by Japanese companies in 2007 as a result of the Bull-Dog Sauce episode are gradually being unwound. For example, we received close to 90 per cent of minority support for a proxy we put forward this past year to cancel the poison pill in GMO Internet.

Because we are in the early innings of engagement in Japan, I believe for the coming few years, engagement will create a virtuous cycle of foreign investment, more engagements, quicker results, better equity performance – and, eventually, the end of Japan being ‘cheap for a reason’.

South Korea: cheap for a different reason

Like Japan, company margins, ROE and, in particular, pay-out ratios are all very low in Korea. Companies are frequently run as if they are the controlling family’s personal capital holding vehicles – which, in fact, they often are. These large and great global businesses have not been great equity investments. They remain cheap for the reasons of family control, interrelated company networks and minority shareholder abuse.

Developments in corporate governance: Korea is in the beginning the early throes of its own corporate governance revolution, with the government spearheading the movement. The current government swept into office after the Elliott Management Samsung saga, where Elliott’s attempts to stop a merger that was abusive to minority shareholders within the Samsung group ultimately led the vice chairman of Samsung, Jae Yong Lee, to bribe Choi Soon-sil, a good friend of then-President Park Geun-hye, to influence the national pension to vote in Samsung’s favour. All of the people involved (the Samsung vice chairman, the President’s friend and the President) ended up in jail. The new president, Moon Jae-in, was elected on a mandate to eliminate cronyism, improve corporate governance and equity market valuations and stamp out the rampant minority shareholder abuse. The new president Moon appointed so-called ‘chaebol sniper’ Kim Sang-jo as chairman of the Fair Trade Commission. Kim was known back in 2004 as the only activist in Korea to be thrown out of a shareholder meeting.

Korea published its Stewardship Code and revised its Code of Best Practices of Corporate Governance in 2016. In December 2017, shadow voting was abolished and a mobile voting system was introduced to ease shareholders’ access to general meetings. In February 2018, the Financial Services Commission (FSC) announced a plan to facilitate and encourage minority shareholder participation at meetings for listed companies, among other things.

Opportunities: Oasis was the first foreign signatory to the Korean Stewardship Code. Korea’s National Pension Service (NPS), the world’s third-largest pension fund, adopted a stewardship code this year. That endorsement is substantial, as NPS owns key stakes in nearly every major company in Korea and often holds the tipping vote between family ownership and institutional and retail shareholders.

As a testament to companies’ increased vulnerability, this year has already seen Elliott target one of the country’s most recognisable names: Hyundai. its campaign in Hyundai Motor Group to stop an abusive acquisition echoes its campaign in Samsung Electronics, which helped kick off the corporate governance revolution in Korea.

In addition to Elliott, there are a growing number of domestic activists. While the investment universe in Korea in terms of market capitalisation and industry remains dominated by a small number of family-controlled companies, or ‘chaebols’, we believe Korea’s corporate governance revolution – in practice, a revolution against the chaebols (‘Chaebolution’) – can happen very quickly. There have been several false dawns in South Korea in the past, but we would not be surprised to see a very different South Korean investment landscape in two years. If Chaebolution does sweep across South Korea, we believe pay-out ratios will improve dramatically and, with them, equity market valuations.

Hong Kong: a tale of two cities, err, I mean two systems

The Hang Seng Index (HSI) is dominated by two very different kinds of companies: the new entrepreneurial class from China – companies that are growing fast and whose valuations reflect that growth (Tencent is nine per cent of the HSI) – and the older, stogy, often second- or third-generation property, ports, infrastructure and banking businesses in Hong Kong that trade at much more modest prices. The most prominent and publicised corporate governance battles have been fought in the second category, where one can observe the most significant discounts to book value and abysmal ROE compared to global peers, a sign of both investor frustration and a lack of accountability and where shareholder engagement is needed the most.

The Hang Seng Index (HSI) is dominated by two very different kinds of companies: the new entrepreneurial class from China – companies that are growing fast and whose valuations reflect that growth (Tencent is nine per cent of the HSI) – and the older, stogy, often second- or third-generation property, ports, infrastructure and banking businesses in Hong Kong that trade at much more modest prices. The most prominent and publicised corporate governance battles have been fought in the second category, where one can observe the most significant discounts to book value and abysmal ROE compared to global peers, a sign of both investor frustration and a lack of accountability and where shareholder engagement is needed the most.

Developments in corporate governance: Hong Kong is in the midst of its own Stewardship Code adoption, albeit at a much slower pace. In 2016 the Hong Kong Securities and Futures Commission published its ‘Principles of Responsible Ownership,’ otherwise known as the Hong Kong Stewardship Code. The Principles are similar to most stewardship codes, asking investors to monitor and engage with investee companies and have robust policies for executing, monitoring, reporting and enhancing their stewardship activity. The Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX) published its proposed revisions to the Corporate Governance Code and Listing Rules in November 2017. The proposed changes aim to address corporate governance concerns, such as independence, ‘overboarding’, the responsibilities of the nomination committee and board diversity.

Opportunities: Because of structural hurdles in Hong Kong, including large family ownership structures that effectively make many companies in Hong Kong very closely held, the tight relationships between pension managers and corporates and the large percentage of passive retail, there have not been many successful engagements with management. There has been some history of stopping abusive transactions, but there are still many more companies plagued by low asset turnover, low ROE and years of poor share performance that look like they could use an engaged shareholder base. The recent dual share class amendments implemented in Hong Kong (read: super voting shares for founders), will also hamper engagement going forward.

Still, there have been some successes, with a smaller number of active and public engagements with management and few winning victories over management recommendations – but they have been few and far between. David Webb, a well-known private investor and advocate for shareholder rights and market transparency in Hong Kong, has led his own battles and continued publicly to call out bad behaviour when he sees it. Shareholders blocked the abusive attempted merger of Power Assets with Cheung Kong Infrastructure and, in a separate case, banded together with our own efforts to protect shareholder interests in Yingde Gases. Other notable cases include BlackRock’s public (and ultimately losing) battle to protect its interests against a dilutive issuance in G-Resources, the battle over Convoy Global Holdings and Elliott’s fight with management at Bank of East Asia.

In order to stall the long march to irrelevance as it competes with Shanghai for liquidity and with New York as a tech listing destination, the success of Hong Kong’s corporate governance is important as Hong Kong seeks to differentiate itself from the mainland as an investment destination.

Singapore: cheap for all the reasons we’ve talked about

Dominated by real estate, resource and ports, many companies in Singapore’s benchmark STI index have been listed for more than 50 years. These are second-, third- and fourth-generation businesses in the hands of professional management – making their equity cheap for familiar reasons.

Dominated by real estate, resource and ports, many companies in Singapore’s benchmark STI index have been listed for more than 50 years. These are second-, third- and fourth-generation businesses in the hands of professional management – making their equity cheap for familiar reasons.

Developments in corporate governance: Singapore, in constant competition with Hong Kong, has also made serious progress in setting up a framework for successful shareholder engagement. Singapore released its stewardship code, called the Singapore Stewardship Principles for Responsible Investors (SSP), in November 2016.

Singapore’s Corporate Governance Council released a paper in January 2018 with its recommendations for revisions to the Code of Corporate Governance, encouraging improvements like greater director independence, enhanced board diversity and board renewal, among other measures. Singapore also has a number of useful tools and resources for activist investors, including the powerful lobby group, Securities Investors’ Association Singapore (SIAS), whose questions Singaporean companies are encouraged to respond to at their AGMs.

Opportunities: Singapore has hosted some shareholder battles and there is a recent history of campaigns that have borne some fruit (like Hong Kong, this has happened off a very low base). Singapore’s legal authority is in place; now shareholders must increase their engagement. Singapore shares the same issues with many other jurisdictions in Asia, where there are significant family holdings controlling more than 30 per cent of the shares outstanding, often not working to maximise shareholder value, with the occasional (very painful for investors) related party transactions at depressed prices diluting value for minority shareholders. These families eventually will need to make a decision as to whether or not they need the market. A decade of low interest rates has made equity financing look too expensive, but with the decline in equity (but certainly not asset) valuations over the same time period, current prices make equity financing untenable. In a normalised rate environment, controlling shareholders will have to make a choice on whether or not they want to adopt reform policies to reopen the market.

Singapore has the distinct advantage of having Singapore’s sovereign wealth as an enormous public market investor. Temasek’s leadership in improving governance, encouraging buybacks, cheering mergers and encouraging management to do more to increase corporate value can act as a significant impetus to kickstart a virtuous cycle of corporate governance improvement. As a result, unlike Hong Kong, Singapore has a far greater ability to pull the levers of public policy in order to support significant improvements in governance and with it equity returns.

China: growing fast, so shareholder haven’t needed to focus on CG – yet

China is growing fast, so shareholders have not needed to focus on corporate governance – yet. The most actively traded market in the region, China is dominated by entrepreneur-run companies and state-owned enterprises (SOEs), with the most growth potential and the widest and deepest moats protecting management.

Developments & opportunities in corporate governance: China developed its corporate governance code under the leadership of the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) in 2001. This was further updated in 2011 and reviewed again in 2016. And yet, in this early stage of development, China’s corporate governance wave has yet to develop. In general, the shareholder bases have not been ‘institutionalised’ enough yet to create a framework of responsible engagement.

In some ways, mainland China offers regulations that many Western investors could only dream of, with very strict sentences for those convicted of corporate fraud (including the death penalty). There are often far more serious penalties faced for committing frauds in China than are faced by Chinese executives for committing fraud on foreign investors in foreign markets – where executives behind some of the most famous Chinese frauds remain free without facing much personal consequence, let alone the prospect of regulatory or criminal liability.

Mainland China also blocks controversial ‘dual-class shares’, something that the US, Singapore and now Hong Kong have permitted. For foreign, long-term investors in search of high return, owner-operator businesses, China is probably the best hunting ground. However, uneven application of the law and that some entrepreneurs view their relationship with minority shareholders as adversarial (not unlike Carnegie or Rockefeller in their time) means that shareholders still face considerable risk if their interests and the founder’s interests ever diverge.

There has been a smattering of campaigns, typically led by large individual shareholders rather than institutional investors. In the broad context, investors have been willing to forgive the poor corporate governance, including the VIE structure and dual-class share structures of foreign listed mainland businesses. The state-owned enterprises

and largest companies have now enshrined in their corporate documents the special place the Communist Party holds in their governance structure and shareholders have had no choice but to accept it. For now, shareholders can complain, point out abuse or fraud, or flee. Market openness to genuine engagement is still distant.

Taiwan: Cheap(ish) for common reasons

The fast growth of the tech-heavy Taiwan market has slowed, but valuations have not yet come down to very attractive levels for value-biased engaged shareholders.

Developments & opportunities in corporate governance: Taiwan published its Stewardship Principles for institutional investors in 2016, which encourages investors to monitor and dialogue with investee companies. Since 2017, all companies are required to have at least two independent directors and 20 per cent board independence and to disclose the gender of directors. The Taiwan Stock Exchange also made changes to its Corporate Governance Evaluation System to place further emphasis on e-voting and English disclosure, which has been mandatory for all TWSE/TPEX listed companies since 1 January 2018.

While we believe there are many Taiwanese companies that can use improvement, close family ownership has so far prevented engaged shareholders from being effective. More explicit government support would be helpful here.

Indonesia: not yet

Developments in corporate governance: Not yet. Nat Rothschild’s bruising and losing experience in Indonesia with Bumi and the Bakrie family provides a cautionary tale for any activist shareholder. Bumi, an Indonesia-focussed coal miner, was created by effectively injecting the Bakries’ Indonesian mines into Rothschild’s London-listed shell. In a messy, public five-year meltdown, Rothschild and the Bakries fell out over the company’s governance. Still, teaming up with a powerful Indonesian family, as hedge fund Argyle Street Management did to launch an offer at the end of the Bumi saga, seems to be the only practical path.

Further separation of Indonesia’s powerful family interests and the judiciary would help governance and valuations dramatically.

Malaysia: Cheap for all the reasons

Malaysia has had its share of issues and some of the ‘corporate governance discount’ is self-inflicted. There is a new government in office following the 1MBD scandal (which was so vast in scope that I’m not sure ‘bad corporate governance’ adequately covers the numerous failures and issues involved). Like other British colonies, Malaysia’s legal system is shareholder-friendly, but success also requires a fair judiciary and a robust legal system, free from political influence.

Developments & opportunities in corporate governance: In 2017, Malaysia released its newly revised Corporate Governance Code which further encourages meaningful disclosure, ethical behaviour, accountability and transparency. As the code states, ‘companies that embrace these principles are more likely to produce long-term value than those that are lacking in one or all.’ They call this ‘CARE’ – an acronym for Comprehend the spirit of the code, Apply the best practices and Report meaningful and accurate disclosure. I’m happy to continue to monitor the Malaysian market from afar for now.

India: not cheap. Investors have accepted the trade-off of poor corporate governance for growth

Investors have accepted the trade-off of poor corporate governance for growth and India has been one of the best-performing markets over the past one-, three- and five-year periods.

Developments in corporate governance: The Committee on Corporate Governance published a report recommending revisions to the Securities & Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations & Disclosure Requirements) Regulations in October 2017. The proposed recommendations included a proposal for a Stewardship Code for institutional investors and focussed on related party transactions, transparency, board structure, director independence and disclosure (among other areas).

Additionally, the previous Congress-led government introduced a new Companies Act that introduced e-voting and gave shareholders a vote for every share they held. It’s worth noting that the Indian regulatory framework and rules for takeovers and delisting offers are not unfriendly to minority shareholders, as the former colony’s rules are based on the UK Takeovers Code.

Opportunities: India is also seeing a bit of a rise in shareholder activism in companies that have not delivered on their side of the growth bargain. That includes rejections of pay increases at Tata Motors and the blocking of sales to related parties at below fair market value at Raymond Ltd. There have been a number of other proxy battles to gain board access, including in 2017, when Florintree Advisors proposed a ‘small shareholder’ representative on the board of PTC India, but was not successful. This battle continues.

Similar to China, a number of entrepreneur-led companies and SOEs dominate the market. India has a very developed legal system, though it is a very long and arduous process to use and navigate that system. The government has been prone to incessant change in its foreign investment policies, the most recent of which taxes equity market gains. The market remains cheap, but for different reasons than in most other Asian countries. We are forever interested in ‘incredible India’ and will continue to watch this space.

If I had any advice for India, it would be just to stop changing the investing rules every two years. Investors like consistency.

Australia: a mixed bag

Australia continues to grapple with the competing calls of independence and foreign investment. Often described as the ‘most over-brokered market’ in Asia as the result of brokers and investors looking to return home to Bondi after years in Bangkok, Osaka and Singapore, Australia has had a surprising number of frauds, self-promotions and over-inflated company valuations, given its robust regulatory system and open disclosures.

Developments & opportunities in corporate governance: Australia is open to engagement and some large shareholders are engaging some of the country’s largest companies. The rules make engagements easy: like Japan, Australia has low thresholds to call an EGM and requirements for consistent supermajorities for executive pay. In terms of corporate governance development and the way the market and investors perceive the aggressiveness of shareholders, I would say Australia is mid-way between the UK and the US.

The single most important market structure feature in Australia is the giant superannuation funds, which make institutions the single most important investor base. This has led to success for ‘home-grown’ Australian activists who can marshal those investors, such as Gary Weiss, who won a resounding victory in his Ariadne fight and allowed Elliott to have some degree of success with BHP.

Engaging the superannuation funds and getting these typically conservative investors to vote with activists has been the biggest challenge. The best opportunities come when those board or management actions are so egregious that they meet the high investor hurdle for support. Hence, while there have been numerous engagements with successful board representation granted in the past few years, for large- scale and transformative engagements to be successful, activists in Australia still need to make a very compelling case.

Closing thoughts and looking ahead

Of the typical demands of shareholder activists, the most common in Asia to date have focussed on improving return of capital, board representation and investor relations and opposition to announced M&A. Interested–party transactions and transactions within conglomerate structures seen as being undertaken just to further a founder’s influence are increasingly reviewed and opposed.

It is still early days in the ‘engagement’ (the term of art in Asia), or activist landscape. Corporates are just beginning to understand what these shareholders want, how they approach companies and how to address their concerns. The encouraging news is that governments, from Japan to India, have now demonstrated how important they believe corporate governance is to increase foreign investment, lower the costs of capital and invigorate corporates and with them, their economies. Governments now understand that this comes cheaply, as engaged shareholders work on improving their corporates for ‘free’ and management or the board can use the help and guidance, as opposed to an investor set that runs as soon as they see something they don’t like.

As more shareholders engage, more shareholders vote their interests and more corporates improve, everyone wins.

Footnotes:

2. According to SharkRepellent and Activist Insight as of March 1, 2018.

5. IR Japan data as of June 2018