In 2001 I wrote an article in the Wall Street Journal, under the headline of Japan’s Coming Shareholder Revolution.

The timeline I had in mind in 2001 was five or 10 years, not 18 years. But neither did I correctly predict the rapid acceleration in the pace of reform over the past four years, in which I myself have played a role. Here is a status report.

Regulators, the GPIF and the TSE are maintaining momentum

Unlike in 2013, when I first proposed it, Japan now has a Corporate Governance Code (CGC) and it has already been revised once. The new revisions require companies to either have a majority of independent directors, or at least have an ‘independent’ nominations or compensation committee with a majority of outside directors. The revised CGC also has more stringent principles about ‘allegiant shareholders’ (so-called cross-shareholdings) and requires companies to disclose their policy for reducing them. Furthermore, as the outcome of an advocacy drive I started several years ago, the CGC now includes an entirely new principle, effectively asking companies to direct their own pension funds (some of the largest asset owners) to sign the Stewardship Code (SC). This is a very symbolic change.

That Stewardship Code, also has been revised and now contains something I proposed to absolutely deaf ears in 2010: the disclosure of per-agenda-item votes at AGMs. This is having a big impact. Japan’s huge national pension fund, the GPIF, is pushing its asset managers hard on environmental, social and governance (ESG) integration and now publicly refers to ‘corporate governance codes’ in its policies for stewardship and proxy voting – something it did not do when the CGC was first put in place. The GPIF’s push for ESG-based investment has made those three capital letters almost a household word, a big change from just a few years ago. The Japan Exchange Group (JPX/TSE) now requires something I was told would be met with the most extreme resistance in 2014: disclosure about ex-CEOs who hold ‘advisory’ positions that carry no legal liability but enable them to meddle in strategy to protect their legacies and obsolete preferences.

As a result of a myriad of regulatory and framework changes like these, more than one-half of TSE1 companies now have three or more outside directors, something that was unthinkable just a few years back – as was the mere mention in the CGC of the words ‘a majority of outside directors’.

Relative to where we were in 2013, these and other reforms amount to massive progress. But one day, regulatory fatigue will inevitably set in. The FSA will increasingly point out that ‘at this point, improvement of governance and returns is mostly up to investors’. And, the JPX/TSE takes its cues from the FSA.

Both foreign and domestic investors are finding their voices

Luckily, investors are now stepping into the fray. More investors are making demands (or polite suggestions) to companies as part of the government’s policy to promote ‘constructive engagement’ and are serving up ‘against’ votes on AGM resolutions that send a clear message – such as director appointments and takeover defence plans.

Consider the following recent trends:

1. There were more shareholder proposals in 2018 then ever before (a total of 42 according to the Nikkei Newspaper, or well over 50, depending on how one counts). Two of them were approved this year – and more if one includes cases where the company complied partly or wholly before or after the AGM (see Figure 1, below).

2. The increase is largely made up of shareholder proposals that focus on governance-related issues, ranging from director and corporate auditor appointments, to cumulative voting, to separating the CEO and chairman positions, to establishing nominations and compensation committees, to changing the legal form of governance used by the company, to mandating the reduction of cross-shareholdings or requiring responsible voting of such shares, to schemes that would better align executive compensation with ROE or shareholder returns and others. Increasingly, activists are drawing from – or directly referring to – key principles in the Corporate Governance Code (or ‘best practices’ abroad) when crafting their proposals, thereby positioning them as ‘reasonable’ and making it harder for companies or asset managers to oppose them.

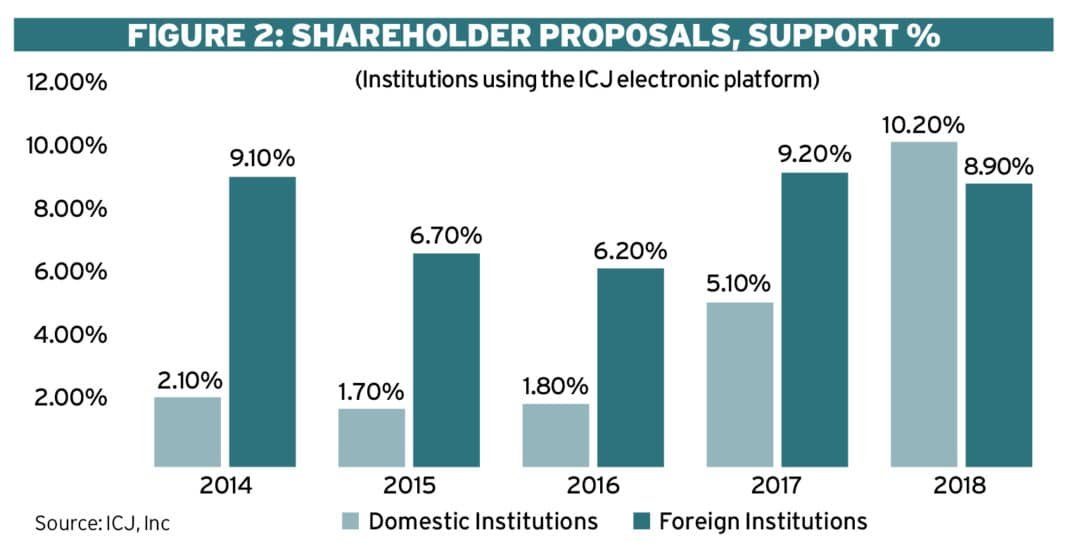

3. In response, more and more institutional investors are voting in favour of shareholder proposals. Consider that only 2.9 per cent of shareholder proposals were supported by the GPIF’s equity fund managers in FY2014, but this zoomed up to 11 per cent in FY2017. Very significantly, this trend is especially conspicuous among domestic investors (see Figure 2, below).

4. Automatic shareholder support for elections of director and corporate auditors is a thing of the past. There are more than a few asset managers where the percentage of ‘against’ votes for director appointments now exceeds 30 per cent; at some it exceeds 50 per cent or even reaches 100 per cent. The ICJ’s average statistics show average ‘against’ voting levels of 10.3 per cent for domestic institutions and 8.8 per cent for foreign institutions. The level is now higher for domestic investors (see Figure 3, below)!

As a result, the percentage of CEOs with 95 per cent or greater shareholder support has fallen to 50 per cent, down from 63 per cent two years ago. Message to corporate Japan: ‘ROE, strategic vision and managerial performance matter now. You can be kicked off the gravy train early’.

For reasons like these, I think it is fair to say that a ‘shareholder revolution’ based on engagement and the use of voting as a crude ‘stick’ is finally under way in Japan. Further, because domestic institutions are now active, this sea change is no longer dependent on foreign institutions, which means that it is here to stay and will have greater impact.

Reforms and practices that are ‘working’

Compared to the pre-CGC days of 2014, a number of reforms or new practices continue to have a positive impact and/or reflect crucial attitudinal changes.

1. There is a now greater recognition that returns on investment need to increase. This is most often reflected to references to raising return on equity and widespread realisation that returns in the ‘investment chain’ directly affect the health of Japan’s economy and the welfare of its citizens. Executives now feel, and are reacting to, the expectations of society and the markets in this respect more keenly than before.

2. Many more boards than before have two, three or more outside directors and are learning how to cope with reporting to them and the greater accountability that arises from their comments and advice (now recognised to be potentially helpful because of their greater objectivity) even if they may not be perfect choices as INEDs or are ‘over-boarded’.

3. The practice of self-evaluation of the board (by the board) has had a surprisingly beneficial impact, more than I expected when I proposed the concept in 2014 at the suggestion of Frank Curtiss (then at RPMI Railpen). At many companies, Japanese directors are responding to internal surveys with direct, pithy comments and suggestions, which are clear feedback to CEOs and fodder for the secretariat staff to use in proposing practice changes. Directors finally have a forum to which they can submit their comments and complaints.

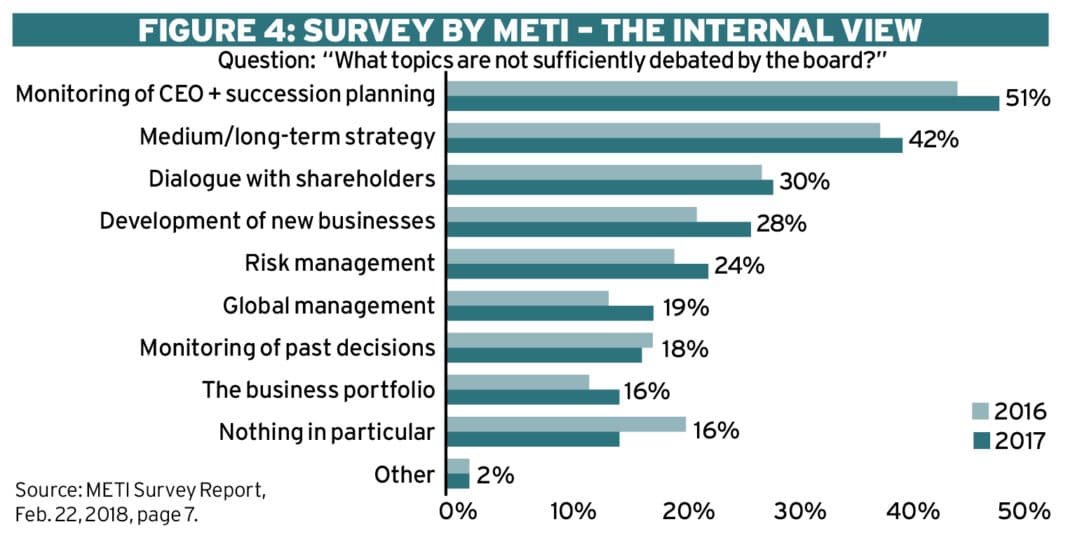

4. There is a widespread public recognition that keeping retired executives (especially CEOs) on the dole as ‘advisors’ can make it difficult for their successors to change the strategy or exercise independent leadership. Companies are starting to react to this change in thinking among investors, the public and the media (see Figure 4, below).

5. There is and increasing

body of analysis that shows various kinds of correlation between modern governance practices and corporate performance. This can now be used by investors to show portfolio companies that governance does in fact make a difference. This includes excellent analysis by METI (now a governance proponent) showing that the existence of nominations or compensation committees correlates with out-performance; or analysis by my own organisation (BDTI) and METRICAL, Inc. showing that ‘out-performance’ correlates with having a majority of independent directors and/or a number of factors that are driven by governance, such as low cross shareholdings, a robust and clear growth strategy, stock buybacks combined with cancellations and incentive compensation.

6. ESG has become so commonly mentioned and discussed that one sometimes fears it will de-prioritise simple governance and remain mainly a fad that asset managers use to raise AUM and companies use as grist for the IR mill. But relative to the past, the trend is an excellent one.

Reforms and practices that are not working so well

1. Efficient engagement Despite all the constant talk about ‘constructive engagement’ and the self-promotional confidence by asset managers that they are having a pronounced impact, to my knowledge not a single institutional investor has set forth detailed proxy voting guidelines that ask portfolio companies to adopt modern practices about the proportion of INEDs, director qualifications, committee structure (role, makeup and leadership), capital allocation, policies for training directors and executives and so forth, along the lines of the CPP’s proxy voting guidelines. I am talking about an appropriate level of detail and some examples. In contrast, many asset managers here appear to believe they are fulfilling their expected role if they merely meet with their largest portfolio companies, discuss the business, state a few concerns orally and get a gut feel for the quality of management.

While it is excellent to have in-person meetings, in my view, relying on such meetings alone is a very inefficient way to ‘engage’ with portfolio companies in New Japan. Preceding such meetings with written suggested practice standards that will guide voting, noting that exceptions will, of course, be made and giving ample advance ‘warning’, would be much more effective and efficient.

Aside from past custom, there are several reasons for the tendency to not leave detail in writing. The first is simply that global ‘best practice’ has been scorned for so long (as in, ‘we are different here; there is no reason to considering doing that in Japan’), that fund managers themselves either still believe that rhetoric to some extent, or fear that it would be rude to suggest specific practices and/or simply do not understand those practices and how to apply them in Japan in an effective manner. In almost all cases, fund managers have never sat on boards themselves and need to study foreign practices more. A second reason is that the word for ‘engagement’ in Japanese suggests merely in-person dialogue and mutual exchange of views, rather than (also) clarity of ‘asks’ that, if not complied with, will result in ‘against’ votes. Or at least, it can be interpreted that way.

The third reason is that certain Japanese IR consultants still circulate to their corporate clients secret ‘blacklists’ of investors who have become ‘very demanding’. Asset managers fear that if their names get on these lists, companies will refuse to meet with them (after all, that is the purpose of circulating the list) and they will be shut off from information flow from portfolio companies. Obviously, they would also be unable to tell their customers that they are doing ‘constructive engagement’ if they were not even allowed to meet with the company.

These fears are largely ungrounded unless one is a true activist, but like a skittish thoroughbred, once a financial institution is ‘afraid of its own shadow’ it will not be convinced otherwise. If the FSA wants ‘constructive engagement’ to maximise its hoped-for benefits, it should be prohibiting the practice of informal blacklists.

2. Reduction of ‘allegiant shareholders’ We still have a problem in Japan that there are far too many shareholders which are not asset managers and whose real purpose in holding shares is not to seek investment returns but rather to obtain or keep business and/or help ‘defend’ the other company by always voting in support of it at the AGM, often receiving the same treatment in return. (In English these shares are often referred to by the term ‘cross-shareholdings’, but often the holdings are only ‘one-way’.)

Most analysts calculate that the percentage of all shares that fall in this category is about 15 per cent of listed company shares, but when other allegiant holders such as banks, insurance companies and corporate-controlled trusts are lumped in, it is north of 30 per cent. My own organisation (BDTI) is now attempting to calculate the percentage of such holders for each listed company on a more precise basis. At any rate, it is easy to see that if the average is anything close to 30 per cent – there will be many companies with levels like 40 per cent, which effectively insulates management from being voted out for anything except the most egregious scandals. Given that, on average, only 70-80 per cent of shareholders vote, even a 25 per cent ‘allegiant shareholder’ base provides a highly effective defence against the voting trends outlined at the start of this article.

Hopefully, the new wording of the CGC encouraging the reduction of ‘allegiant’ holdings will have significant effect via the mechanism of engagement, which will become more ‘efficient’ in the meantime. This combination would be a game-changer.

“I THINK IT IS FAIR TO SAY THAT A ‘SHAREHOLDER REVOLUTION’ BASED ON ENGAGEMENT AND THE USE OF VOTING AS A CRUDE ‘STICK’ IS FINALLY UNDER WAY IN JAPAN”

3. Modern practices for nominations, succession planning and HR in general Although they are growing in number (35 per cent of TSE1 firms now have them), most ‘advisory nominations committees’ are cosmetic in nature. More than half of such committees only meet once or twice a year; at only 42 per cent of them is an outside director the chair; and, on average, only 45 per cent of committee members are outside directors. Because choosing who to ‘promote’ to the board is the source of the CEO’s political power, he often sits on the committee and serves as its chair if possible. This eviscerates the committee’s independence and prevents it from evaluating his performance objectively or getting much input about alternative CEO candidates and up-and-coming executives from other sources. In some cases, the CEO’s performance is not even a valid subject of the committee’s consideration. (After all, he is right in the room.) The situation for ‘compensation committees’ is similar.

To increase the number of firms with committees and to make them more effective, will require two things: (a) specific requests from investors to create committees and ensure their independent composition and leadership, enforced by a voting ‘stick’; and (b) outside directors and investors who insist that companies put in place modern HR practices to evaluate managerial performance and aptitude, map talents and experiences and thereby better inform such committees so that subjective input from the CEO is not the main source of information. I believe that robust incentive compensation plans will only achieve their full desired effect once procedures and criteria for evaluations, promotions and nominations have been made more transparent and objective.[1]

4. Investment in modern executive, governance skills Japan suffers from chronic under-investment in modern management and governance skills through means other than OJT and which would lead to common skill sets in strategic thinking, financial and project analysis and governance practice in the board room or reporting to it. Executives appointed to the board often come to it unprepared to be directors for the first year.

As a survey on director training by the Association of Corporate Legal Executives, concluded in February of 2016, ‘in the past, director training at Japanese listed companies did not emphasise increasing skills for this role [‘monitoring’]… It is necessary to add this aspect…It seems rare that directors have enough knowledge when first appointed…’ Other results from the survey were equally disheartening (see Figure 5, below).

Here again, the specific voices, in writing of investors are needed. The questions, with respect to managers, executives and directors, should not be, ‘what is your general policy about executive and director training?’. Rather it should be ‘who exactly did you actually train last year, in what subjects, how and for how long?’[2]

The bottom line: It’s up to the investors

Going forward, if shareholders ask for specifics, more and more Japanese companies will heed their reasonable requests. The more numerous such investors are, the faster Japanese companies will improve both practices and returns. Now is the time to make sure your voice is heard, not the time to play free-rider.

Footnotes:

- Such incentive compensation plans should also include many of the less senior executives who are not yet on the board.

2. The two most common responses we receive in surveys after BDTI’s intensive director training courses are: ‘now I understand what my role as a director is!’ and ‘I learned how little I know about finance and reading financial statements.’