Shareholder and hedge fund activism has become an influential force in German corporate life over the past 15 years or so, both in terms of corporate governance improvements and value creation, with approximately 400 campaigns launched by 100 (predominantly foreign) activist hedge funds against 200 of the country’s 650 public corporations.

Game changer

Until recently, it was the threat of hostile takeovers that was deemed the principal corrective for poor management decisions and shareholder value destruction due to performance failures. Today, in Germany it has shifted to active monitoring by engaged or activist value minority investors – characterised by such an alignment of interests with and persuasion of fellow shareholders and institutional investors to generate support in the form of the requisite general shareholders’ meeting (AGM) majorities, if necessary. With 60 to 70 per cent (sometimes an even higher percentage) of the voting stock of leading German corporates owned by foreign institutional investors, this train of thought must be taken seriously.

There are two significant factors that help contextualise activist campaigns and market acceptance of shareholder and hedge fund activism in the German corporate governance debate.

Firstly, 60 per cent of all 650 German publicly listed companies are controlled or dominated via share block ownership by families, founders, management teams, investors or holding companies. Thus only 250 German public companies lend themselves to the presumption that activism is dependent on a widely-held, dispersed shareholder ownership/population so that when negotiations with target management break down, the activist may resort to launching a confrontational proxy fight in order to replace some or all members of the supervisory board. They, in turn, may recall the management and replace them with new managers who agree with the activists’ strategic plan.

Second, there is a certain consensus-oriented German corporate culture, etiquette and decorum that, over time, has demonstrated how publicity and accusatory campaigns against sitting management or supervisory board, proxy fights or resorting to litigation are by and large unsuccessful strategies, with only 20 per cent of all campaigns ever becoming public knowledge. There has only been one precedent (out of a total of seven attempts) where activists were capable of replacing the chairman of a supervisory board in an adversarial proxy fight – at pharmaceutical company Stada AG in August 2016.

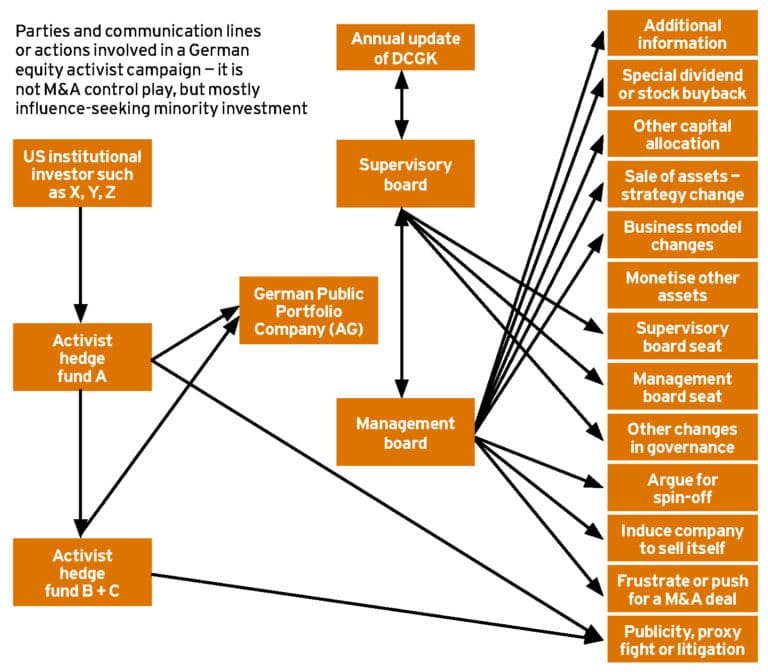

In the view of many, the separation of ownership and control (Berle-Means) and the principal-agent problem (Jensen-Meckling) has recently led to sharp market cap drops and share price value-losses at the expense of shareholders in large DAX 30 German corporations and corporate groups, such as the utilities RWE and E.on, but also TUI, Commerzbank, Volkswagen and Deutsche Bank. It is no secret that concerned institutional investors have initiated discussions with activist hedge funds on these matters (see illustration opposite).

Observers believe that leading activist hedge funds, who acquire usually a minority position in the one to 10 per cent range (seldom more than 15 per cent total, depending on target size), could exert such additional monitoring function on behalf of all shareholders without necessarily destabilising the balance of powers between the AGM (shareholders), supervisory board and management board. First, they are not imposing their views on anybody, least of all management or the supervisory board, but seek to engage and present well-thought out alternative courses of action. Second, they have to win the votes and confidence of fellow shareholders and institutional investors in the first place in order to have any strategic impact.

The informal character of German activist campaigns

So, to recap, there have been approximately 400 equity activist campaigns in the past 15 years or so in Germany, attaching to 200 public targets (out of a total of 650 listed companies), mostly hidden from the public.

Further, assuming a base line of 400 campaigns, Thamm/Schiereck claim that 75 per cent of these samples have been kept under the lid and were never in the public limelight, on social media or mentioned in the press or legal/economic writings, reflecting the mainly informal approach take in these campaigns. This corresponds with our own findings. Over the years, we have only been able to identify 70 to 80 activist attempts at value creation with public German target corporations.

There is another fork in the road and bifurcation of observations. If we assume 400 activist engagements in total, 250 took place before the financial crisis, the remainder thereafter. The early ones were fairly multi-faceted attempts at value creation.

The majority of the subsequent 150 activist interventions since 2009 mostly follow the script of more or less unimaginative takeover arbitrage, by (i) opposing a mergers and acquisition (M&A) transaction as value-destructive; (ii) pushing for a business combination involving the portfolio company as creating value; or else (iii) reflecting an attitude towards a public M&A transaction that could be called supportive in general, except for the consideration promised to the hold-out shareholders who are refusing to sell their stock position to the acquiring entity for the same consideration proffered to all other shareholders – activists simply extract a better price.

Here, at the so-called back-end, activists attempt to negotiate or litigate for additional compensation for their hold-out stock position at odds with the interests of all other shareholders. Or else they block a M&A transaction from the very beginning and attempt to extract better terms for their preferred or convertible stock positions. They need not share this with any other shareholders who receive only minimum compensation for their shares. In the event of the acquirer concluding a domination, profit and loss sharing agreement with the target (requiring a 75 per cent majority), activists follow through with judicial action, seeking a better price for their hold-out position instead.

In Germany, more than 75 per cent of activist interventions following an investment take place in confidential discussions between hedge funds and management and/or supervisory board that never become public. Any communication between company and activist is subject to the mandatory equal treatment of all shareholders pursuant to the section 53a Stock Corporation Act (AktG). If other shareholders so demand during an AGM, management is compelled to disclose to all other shareholders any far-reaching information shared with activists beforehand so long as the piece of information conveyed to such activist investor was tied to their being shareholders of the company, pursuant to section 131 Abs. 4 Satz 1 AktG. From this may be inferred that informal one-on-one discussions are admissible with the result that any other shareholders have no claim to find out the contents of such meetings outside an AGM.

Management and supervisory board are prohibited from sharing inside information with activists (pursuant to section 14 Abs. 1 Nr. 2 Securities Trading Act [WpHG]) unless there are overriding justifications. It is certainly permissible to explain the business model and thereby deepen an activist’s understanding of company strategy – below the threshold of giving away secrets.

Passing on secret information to an activist may only be justifiable if it is in the interest of the company to create exceptions from confidentiality obligations of management and supervisory board (section 93 Abs. 1 Satz 3, 116 Satz 1 u. 2, 93 Abs. 1 Satz 3 AktG).

With their usual average shareholding range between five to 10 per cent, by resorting to informal tactics predicated on personal relationships with members of both boards, activists enjoy the advantage of influencing corporate decision-making directly, with a built-in timing and flexibility advantage, independent of an AGM setting, and their actual weight expressed in the percentage of their stock position in the company.

There is sufficient empirical evidence that, within the already outlined restrictions imposed on company representatives, such personal interfacing is considered the most appropriate means to influence the target corporate leadership for activists and institutional investors alike. Under certain circumstances, the very fact that discussions with an activist have taken place may constitute inside information that is to be made public if such meetings could influence the target stock price appreciably (section 15 Abs. 1 Satz 1, 13 WpHG). It is usually within the frame of a personal meeting or teleconference that activist managers communicate their impressions, provide deeper analysis or air criticism as to corporate strategy and value.

Public campaigns usually happen in only about 20 per cent of all cases. Proxy fights are even rarer and hardly ever successful. The 2007 AGM proxy fight by Wyser Pratte with Cewe Color proved value-destructive, eating up €2.75million of €5.9million corporate earnings after taxes. In this particular contest, because of flawed strategy, the activist neither pushed through a special dividend nor board membership for its four supervisory board nominees.

Parameters for adversarial campaigns and proxy fights

It is important to remember that the management board has the sole authority over a whole host of issues where neither the AGM nor the supervisory board may interfere or intervene. Shareholders may not instruct the management board in corporate structure matters, such as the sale of divisions or subsidiaries or carve-outs, dismissal of workers or employees or in any of the capital structure modifications they would like to see through. It is the management board that is vested with sole authority on a stock buyback programme or special dividend payout. Nor can they officially remove a management board member.

If activist shareholders are dissatisfied with one or several management board member(s), they can build a case and exert pressure on the supervisory board to carry out such dismissal. The direct influence of activist minority shareholders is confined to suggesting (not nominating) members for the supervisory board, causing a special audit when there is suspicion of wrong-doing, or else push for a more aggressive disbursement of corporate earnings to the shareholders.

The suggestion and nomination of new supervisory candidate members has to be agreed upon with the management board, the chairman of the supervisory board or at least an important supervisory board member beforehand behind closed doors.

Should the activist elect to engage in a proxy fight, the management board is obligated to inform all shareholders at the expense of the issuer/company and must express, together with the supervisory board, its recommendation on how to vote on controversial issues. Unlike the US, activists can exploit the obligation incumbent on the issuer to inform all shareholders about the activist‘s motions and agenda items and thus make public their proposals without them incurring any financial charge.

The reverse side of the coin, however, is that shareholders may never burden their proxy campaign costs on the target/issuer – think Sotheby‘s assuming Dan Loeb‘s campaign expenses of $20million – and this is an important variation. As a rule of thumb, a German management board may neither buy back shares held by activists directly in order to get rid of their inherent nuisance value, nor can they make financial concessions in order to broker a compromise or settlement.

Activist minority shareholders in Germany are hampered by two further idiosyncracies in the German proxy process. For one, in the US shareholders have a right to identify the names and addresses of all other shareholders by inspecting the company register. In Germany, however, each shareholder only has the right to inform themselves about the data entered into the registry with respect to their very own stock position (section 67 Abs. 6 Satz 1 AktG). So, activists in Germany are hindered factually from exploring whom they have to reach out to in order to convince them of the superiority of their plan in contrast to the strategy of incumbent management.

An activist may only demand to inspect the participants list of the last AGM pursuant to section 129 Abs. 4 Satz 2 AktG. Given the complexity of custodial chains in modern corporations, this only goes so far. The activist could get in touch with the depositary banks and ask them to pass on the activist agenda to their customers. Finally, an activist could attempt to avail themselves of the Aktionärsforum (section 127a AktG), where it could place a reference to its website (section 127a Abs. 3 AktG), but his is considered a weak tactical avenue.

An activist has to be mindful of acting-in-concert charges in connection with such proxy solicitations (section 30 Abs. 1 Satz 1 Nr. 6 Alt 2 Takeover Code) so that the votes thus solicited are not counted towards their own shareholdings. It can stay clear of this campaign structuring risk if it doesn’t exert its own margin of discretion when voting on behalf of the other shareholders, but sticks strictly to their voting instructions.

A second setback, next to lack of inspection right of the company registry for purposes of identifying and reaching out to the entire issuer shareholder base in Germany, is the German proxy process itself.

“ACTIVISTS IN GERMANY ARE HINDERED FACTUALLY FROM EXPLORING WHOM THEY HAVE TO REACH OUT TO IN ORDER TO CONVINCE THEM OF THE SUPERIORITY OF THEIR PLAN IN CONTRAST TO THE STRATEGY OF INCUMBENT MANAGEMENT”

Unlike in the US, where it is considered sufficient that a proxy advisor receives proxies without the shareholder giving explicit voting instructions, pursuant to section 2.3.2 of the German Corporate Governance Code, the management board should provide for a proxy representative that can cast the votes according to the instructions given to it. It is controversial in the literature whether his casting a vote depends on an explicit voting instruction or whether a blank proxy would do. For credit institutions, a specific voting instruction is required. A general instruction ‘to vote with the management board’ would do. Some argue that the requirement of an explicit voting instruction can be waived if the issuer has designated an independent proxy representative. Should they be an employee of the issuer, this would make a specific instruction advisable (to avoid conflict of interest).

The first successful proxy fight (Stada, August 2016) resulted in replacing the chairman of the supervisory board; six prior attempts (Babcock Borsig (2002), Volkswagen (2006), CeWe Color (2007), Ehlebracht (2010), Infineon (2010), Balda (2012) had failed.

Evidence for improvements and value creation

The Demag Cranes case evidences support for the strong shareholder rights perspective. Cevian Capital through its shareholder rights obtained supervisory board representation by dint of negotiation and actively participated in the firm’s corporate governance. The transaction created substantial value for all investors. Assuming that the shares were purchased at €26 and sold at the increased offer consideration of €45.50 per share, this represents a 75 per cent gain for the investors within one year. Demag’s shares later peaked at €60 and were trading above €50 for most of 2012.

So it appears that in Germany, both the corporate governance framework of listed companies and minority shareholder rights are strengthened in comparison to the US. Cevian is currently invested in Bilfinger Berger and KruppThyssen, having been also engaged earlier with Daimler and Munich Re. Cevian seems to display confidence in the current German corporate environment for engaged minority value shareholders, both in terms of being in a position to influence firm-specific corporate governance measures, as well as minority shareholder protection.

It is very possible for a minority shareholder to gain supervisory board representation. In the cases of KUKA, Deutsche Börse and Curanum there were also changes on the management board level attributable to activist interventions. Although in most instances the board seats were obtained at corporations without a large blockholder, the cases of Deutsche Telekom and Cewe Color Holding demonstrate that board seats can even be obtained in spite of the existence of a large shareholder. The Demag Cranes case shows that (i) minority shareholder rights in Germany are well-developed and strong; (ii) minority shareholders have the opportunity to obtain supervisory board representation; and (iii) minority shareholder activism can have an impact on a firm’s corporate governance.

Interests and strategies of both activist hedge funds and German blockholders defy easy categorisation. Activists aim at creating value expressed in an increased share price of their portfolio companies. They employ intervention and campaigns built around some of the building blocks that we have presented. KUKA demonstrates that hedge funds may align themselves with blockholders to ride a rising stock price. On the other hand, German family blockholders may use activists to attract the interest of international institutional investors following the latter’s recommendations with the ultimate objective of boosting share value and selling their position – displacement through defection. Some activists adapt their strategies to the German context and demonstrate commitment to their portfolio companies, while German blockholders utilise activists to increase the value of their holdings, thus changing their preferences from commitment to liquidity.

Not unlike studies in the US, there are empirical findings in Germany that show there is considerable disciplinary power inhering in activist hedge funds. Virtually all listed companies in Germany (which have shrunk from about 1,000 to 650 in recent years) have an IR department now, monitoring closely their investor base. Many of them anticipate potential investments, interventions and engagements by activists and, in order to thwart campaigns, implement some of the typical activist demands, such as extra dividends, share buybacks or selling non-core divisions.