One of the key trends that I observed in 2018 is the increasing number of organisations that are beginning to view third-party risk management (TPRM) as a board imperative. And with good reason – third parties can have a significant impact on the success and reputation of your business.

The use of third parties – which include suppliers, outsourcers, licensees, agents, distributors, vendors and the like – is an essential part of any business ecosystem today. So much so, that the Institute of Collaborative Working estimates that up to 80 per cent of direct and indirect operating costs of a business can come from third parties, while up to 100 per cent of a company’s revenue can come from alliance partners, franchisees and sales agents.

When your third-party relationships are effective, you benefit from better financial outcomes, innovation and business resiliency. But when they fail, their failures become yours – only magnified.

Keeping track

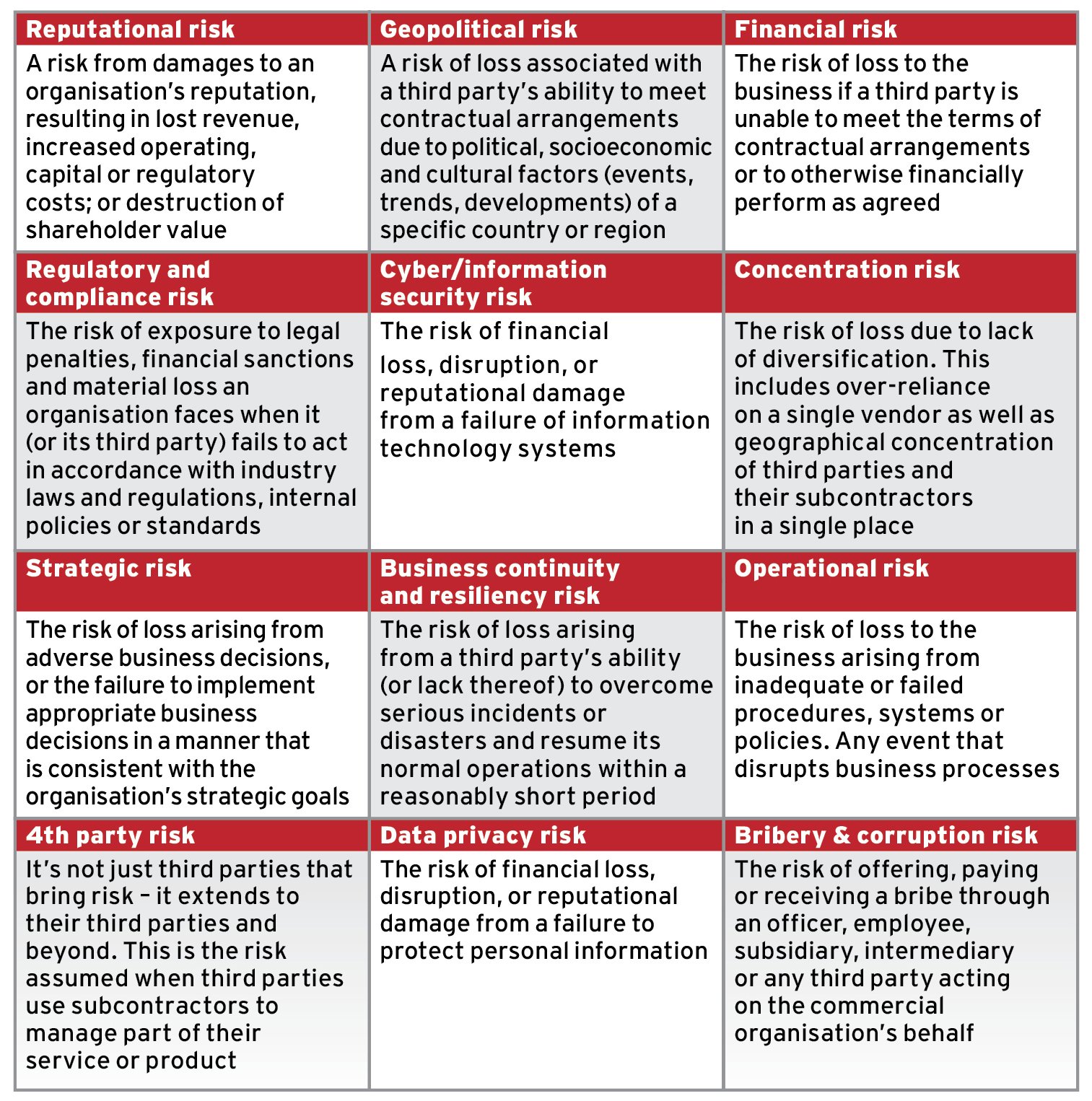

TPRM is a process that allows management to identify, evaluate, monitor and manage the risks associated with an organisation’s third parties and their contracts. With this increased strategic and operational reliance on third parties comes increased risk, which must be identified, understood and managed. This can be a complex exercise as an organisation may have many thousands of third parties and there are many risks that a third party can present, which you can see in the table opposite.

With so much at stake, regulators globally are turning up the heat. They have made it quite clear that while organisations can outsource a task, they cannot outsource the responsibility. Increased regulatory scrutiny, however, is just a symptom of the underlying issue – the way organisations do business is evolving dramatically and rapidly. And with this, the way they manage risk and govern their extended enterprise needs to evolve quickly, too.

This evolution is challenging – third-party risk management is a relatively new discipline and companies are at radically different stages of maturity, depending on their industry, size and culture. From a discipline that has evolved largely from siloed and ad-hoc processes, there’s a growing recognition that a more joined-up, standardised and enterprise-wide view of risk is required.

The role of the board

Progressive boards are recognising that an increased focus on third-party risk makes good business sense, given the importance third parties play in the organisation’s overall strategic approach.

“WHEN YOUR THIRD-PARTY RELATIONSHIPS ARE EFFECTIVE, YOU BENEFIT. BUT WHEN THEY FAIL, THEIR FAILURES BECOME YOURS — ONLY MAGNIFIED… REGULATORS HAVE MADE IT CLEAR THAT WHILE ORGANISATIONS CAN OUTSOURCE A TASK, THEY CANNOT OUTSOURCE RESPONSIBILITY”

In fact, Deloitte believe that ‘those organisations that have a good handle on their third-party business partners, cannot only avoid the punitive costs and reputational damage, but also stand to gain competitive advantage over their peers, outperforming them by an additional four to five per cent ROE, which, in the case of Fortune 500 companies, can mean additional EBITA in the range of $24-500million’.

But there’s more to board oversight than fiduciary duty. There is a bigger purpose, which has far-reaching implications. Ethical boards and the ‘tone from the top’ that they and their C-suite deliver, are integral to ensuring that the business acts with integrity and keeps bad business practices – such as corruption, human rights abuses or environmental crime – from their wider business relationships and supply chain. Put simply, boards are not fulfilling their oversight responsibilities if they don’t take measures to lead ethical business practices across the enterprise, which includes the third-party ecosystem.

Research indicates that an organisation’s ability to effectively mitigate third-party risk is tied to greater board involvement. In the Shared Assessments programme and Protiviti’s latest examination of the maturity of vendor risk management, it reported that there is a strong correlation between board involvement in TPRM strategy and TPRM programme maturity.

Yet, despite the importance of third-party risk mitigation, only about five per cent of risk professionals feel they had an optimised programme in place, according to a 2018 survey conducted by the Centre for Financial Professionals (CeFPRO) and Aravo. Clearly, there is still significant work to be done when it comes to achieving the levels of TPRM maturity we need to protect stockholders, employees and society at large, as well as comply with evolving internal and external compliance requirements.

What is best practice for TPRM?

An organisation with a mature, agile TPRM strategy has immediate enterprise visibility into third-party risk at every level: an overview of the inherent risks across the third-party portfolio, a robust risk profile of each individual entity and insight into third-party performance related to specific contracts or KPIs. To achieve this level of insight and confidence, organisations can follow a few interrelated best practices:

A federated approach A balance of centralised risk management responsibility with participation from business owners and relationship managers allows organisations to standardise TPRM policies and procedures. As a single source of truth across risk domains, a federated TPRM system can generate insights the board needs for high-level oversight as well as be alerted to risks that might be overlooked when information is in silos. For instance, in a disconnected system, leaders may not realise that a third party has relationships in multiple critical areas and underestimate the risk they present to the organisation. If that third party crossed a risk threshold (like a change of ownership that signalled a corruption risk), it’s possible that not everyone would be alerted

Management of the entire life cycle Assessing third-party risk isn’t a ‘one and done’ exercise. Between onboarding and termination, a third-party’s risk profile can change, or they may fail to meet contractual obligations and have to go through a remediation process. Juggling documents and spreadsheets for ad hoc TPRM processes or cobbling together disconnected silos of TPRM practice won’t provide the enterprise visibility you need to fulfil your oversight obligations. The organisation would also be squandering valuable resources trying to analyse and report on data across the third-party ecosystem while increasing potential exposure to unforeseen risks

Enterprise visibility While the board sets the tone for creating a culture of ethical behaviour and accountability, multiple people are responsible for executing, sustaining and auditing TPRM policies and procedures. Most of those people also have other responsibilities as well, so it’s important that they can easily and securely receive notifications and view the data they need, based on their roles, whether in a high-level dashboard, detailed reporting, or by drilling down into specific records. As the centralised system of record, TPRM must be able to deliver an enterprise view of the data, based on the user’s role in the organisation

Secure agility In addition to changes in risk profile, internal policies and regulatory requirements also change, so organisations need to be able to adapt without prolonged or complicated projects. For instance, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that came into force last year meant that organisations that hold or processed personally identifiable information for EU citizens will have needed to evaluate their portfolio of third parties to identify which came within the scope of the regulation, assess them for their compliance posture, and ensure reporting and escalation processes were in place for reporting to the regulators. With new regulations, like CaCPA (California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018) coming online, organisations can’t afford to be locked in to rigid systems

Building effective TPRM oversight

1. Identify your risk appetite

As part of their oversight responsibility, board members should agree on and articulate what is an acceptable risk and what isn’t. Obviously, there are third-party behaviours that can’t be tolerated, such as clear ethical and criminal violations, but somewhere between the impossible goal of zero risk and unacceptable behaviour, there is a point at which the organisation is willing to accept the risk-to-value ratio.

Understanding and evolving the level of acceptable risk requires input and counsel from board members. Larger or more complex organisations may determine varying risk appetites, based on factors such as geography, division or risk type. Certain kinds of risk (such as establishing a critical third-party relationship in a country with high incidence of corruption) call for greater due diligence than others (such as warehouse janitorial services). These thresholds should be built into the TPRM system to trigger automatic warnings and remediation when they are exceeded.

2. Create and support a governance structure

Consistent policies and procedures make it possible for an organisation to identify, analyse and manage risk in a way that can be communicated both internally and externally. To oversee the execution of policies and procedures, many boards are appointing a specific director as the point-person for third-party risk. Some are also establishing managing boards in regions or business units to reinforce both the guidelines as well as the culture of ethical behaviour and compliance.

Balancing centralised risk management responsibility with participation from business owners and relationship managers allows organisations to standardise TPRM policies and procedures without having to run a ‘risk business unit’. By investing in technology that automates processes and empowers employees to manage risk in a federated system, organisations can impose centralised control without sacrificing overall productivity.

3. Clearly define roles and responsibilities

With an overall culture of compliance, there should be clear expectations and accountability across all three lines of defence: 1. Those who own and manage risk (e.g. a business owner or relationship manager), 2. Those responsible for overseeing risk management or compliance (e.g. a risk and compliance executive) and 3. Those who validate compliance with third-party policies and procedures (e.g. internal auditors).

By working collaboratively, these roles efficiently provide the needed third-party risk documentation and reporting, oversight and accountability, and independent reviews. When roles aren’t clearly defined, TPRM may not be given the priority and attention needed to protect the organisation from external risk.

4. Review regularly

Alarmingly, a 2018 survey by EY found that only 22 per cent of organisations report breaches to their boards. Even with the most robust system for managing and understanding third-party risk, the board needs to maintain ongoing oversight. Management should be expected to report on critical KPIs and significant changes, remediation/residual risk and critical relationships that could impact the organisation’s financial or reputational performance.

The board should review the overall TPRM strategy annually to ensure that it stays current with organisational goals and the business ecosystem. While it shouldn’t require a complete overhaul, factors such as a change in risk appetite, new initiatives that introduce new risk domains, and changing legislation or enforcement guidance will require adjustments to TPRM policies, procedures and processes.

Regulatory expectations of board members

Recognising the ethical leadership role of board members, regulators are holding them accountable for poor behaviour, which could lead to board shake-ups and even personal liability. Board minutes should reflect board input, review and approval of TPRM strategy as well as remedial actions. Some of the things regulators expect to see included in board minutes of compliant organisations include:

A record of attendance and participation in regular third-party review meetings

The methodology for categorising critical activities

The approved plan for employing third parties for critical activities

Third-party contracts for critical activities

A summary of due diligence results and ongoing monitoring of third parties involved in critical activities

Results of periodic internal or independent third-party audits of TPRM processes

Proof of oversight of management efforts to remedy deterioration in performance, material issues or changing risks identified through internal or external audits

Embedding TPRM governance in the organisational culture

The role of the board in gaining the acceptance for a TPRM governance programme can’t be overstated. Without organisational buy-in, it’s unlikely the programme will deliver the desired value and results. Creating and sustaining this buy-in requires ongoing support and monitoring as the programme is rolled out as well as over the long term. To help ensure the governance programme is being accepted by the organisation and delivering value, boards should:

- Provide the right resources for the team implementing the governance programme

- Encourage effective collaboration between risk, compliance, procurement, and the business, among other teams

- Incentivise or reward achievement of TPRM organisational metrics (such as through MBOs), when appropriate

- Implement high-quality training for employees involved with third-party relationships

Communicate the importance of TPRM across the enterprise, starting at the top - Invest in a technology platform that reflects best practices and enables effective collaboration, communication, and relationship management

Overseeing a strong TPRM programme demonstrates the board’s commitment to the financial and ethical integrity of the organisation they lead. It helps to ensure their organisation can deliver the value it should be creating for shareholders, improve relationships with third parties and key stakeholders (such as industry regulators) and uphold fair business practices.