EB: What do you see as the current pitfalls of board evaluation?

AW: First, let’s take a look at the big picture. Business and global markets are undergoing a profound transition, from a short term, shareholder or mainly commercial focus (or smart boards), to a longer-term, stakeholder focus, (or wise). As we’ve previously argued in this journal, overconfidence, biases, sub-par organisational structures and financial pressures can all lead accomplished leaders with seemingly robust moral compasses to make poor calls. This can cause huge reputational and financial damage, and we’ve seen a host of headline-dominating scandals and resignations in the last few years. In emerging markets, there are even more systemic weakness in governance – firms either don’t buy into the frameworks that may be in place, or actively misuse them.

So, we can describe wise board leadership as holistic and ethical. It takes multiple perspectives into account. It’s fundamentally about business – via good governance – earning operating legitimacy. It’s a matter of sustainability – as summarised by environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria. Smart boards become wise(r) when they holistically address socio-economic and environmental business dilemmas. They don’t just create and capture vital economic value; they build better organisations.

And this is becoming materially more important. A recent survey from Oxford University’s Saïd Business School and Harvard Business School, found that 82 per cent of investment executives now look at a company’s ESG information, spurred by growing client demand or formal mandates. But they face incompatible reporting across firms and a lack of reporting standards.[1]

Now the question is the extent to which the approach to board evaluation is evolving into an assessment of ‘sustainable board governance’. Here I’d argue that there is a considerable way to go, even in more mature markets that are guided by clear governance codes, such as the UK or South Africa. South Africa’s King IV contains the concept of ‘corporate citizenship’. This embraces non-financial criteria, such as ethics, sustainability and customer care. In short: ‘doing the right thing’ and in a sense ‘bigger’ than ESG criteria. It is for each board to specifically tailor the concept to their individual business.

The core issue is how to transcend conformity or box-ticking in board evaluation, To move from a smart to a wise approach. Asking whether as a board you’re satisfied with sticking to the letter of the codes or also consider the spirit of the codes and strive for a higher level of moral excellence.

When you drill this down to an organisation’s attitudes to external board advisory services, these have been a mixture of ‘grudge purchase’ and ‘reflective best practice’ (with a slight emphasis on the former). One-off engagements tend to be standard procedure, sticking to the letter of the codes. So, there needs to be a shift from cost focus to investment focus. And investment is directly proportional to quality of service and rigour of process.

Currently, this process typically encompasses assessment in-house, online surveying using basic metrics, perhaps supplemented by face-to-face interviewing and consolidation of the insights. This leads to questions of objectivity and depth.

A recent Harvard Law School Forum in conjunction with EY reviewed the most recent proxy statements filed by companies in the 2018 Fortune 100.[2] Only around one in four disclosed using (or considering) an independent third party to facilitate board evaluation at least periodically or combining questionnaires with interviews. There is a fundamental pitfall here. Due to the infrequency of board meetings throughout any given year and the long-term nature of board deliberations, there’s a lack of pull through into consistent improvement over multiple periods when using ad hoc external assessments or self assessments.

So, the first recommendation is a multi-year ‘programme’ approach. Global best practice would be to generate a set of engagements involving a depth of reflection across individual and collective performance, board processes and effectiveness, governance developments and strategy contribution and results over the short, medium and long term. A longer view also allows regulators and shareholders to assess the board’s commitment, both to ongoing measurement, and improvements in board practice.

EB: What would that programme look like in reality?

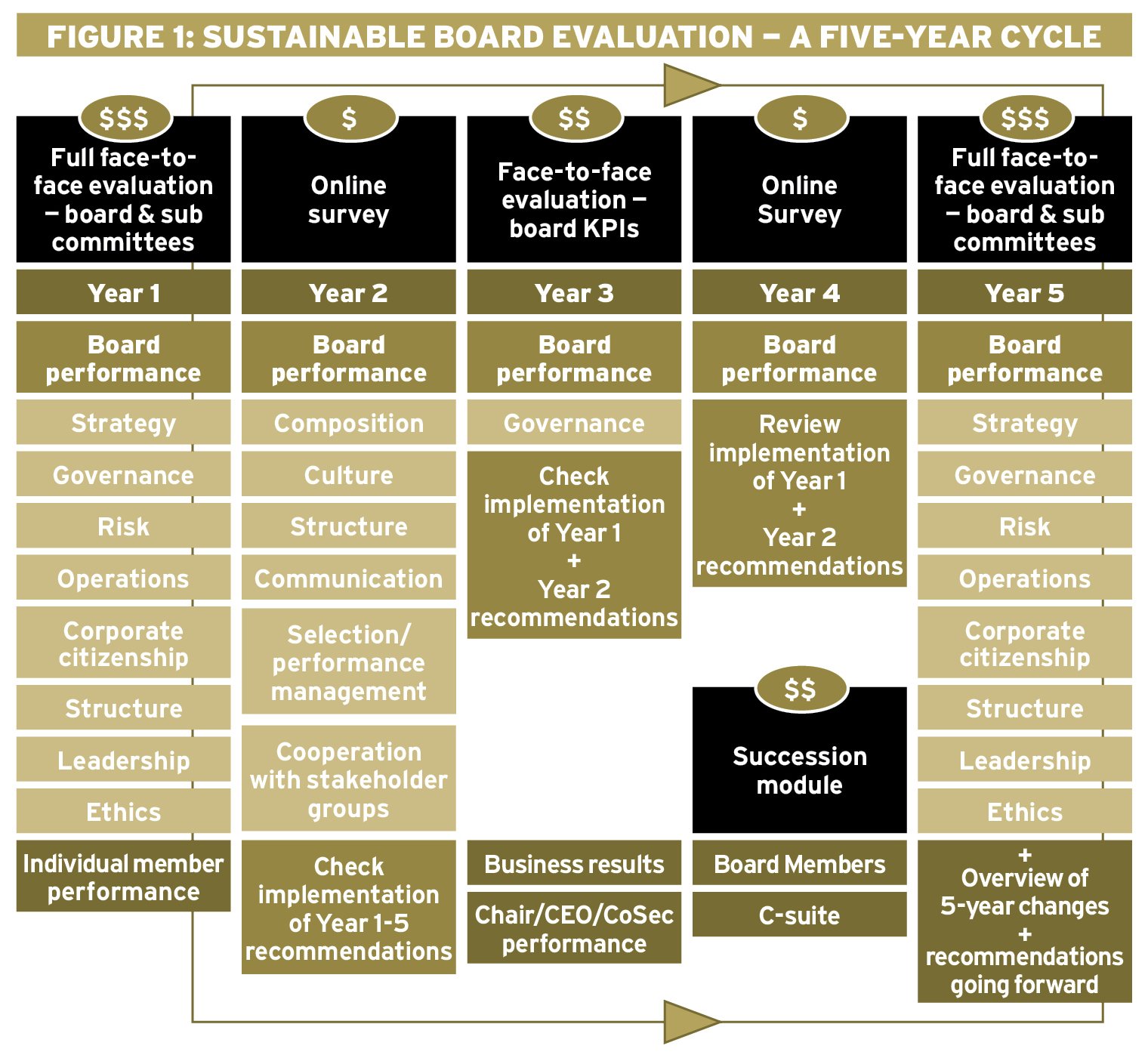

AW: When you consider financial auditing, for example, auditors often spend five or more years with a client before forced rotation (in some markets). Similarly, I’d argue for a three- to five-year programme, alternating between full board evaluation and online surveying, and including face-to-face interviewing. This should include a succession module at least once every five years (see Figure 1, below).

EB: What about different markets that face different cultural paradigms – Africa and Germany, for example?

AW: This three to five-year cycle is customisable to processes and marketplaces.

Organisations must ask whether they need a clear and public board behaviour framework, or only some guidelines? This often depends on the operating country, regulators and bourse compliance in the area of activity. It also stems from the company itself, whether public, private or non-profit. What is clear is that good governance codes certainly support a framework in the minds of investors and directors concerning what best practice is, as agreed by both sides.

EB: You mentioned wise leadership. How could you build that into board evaluation?

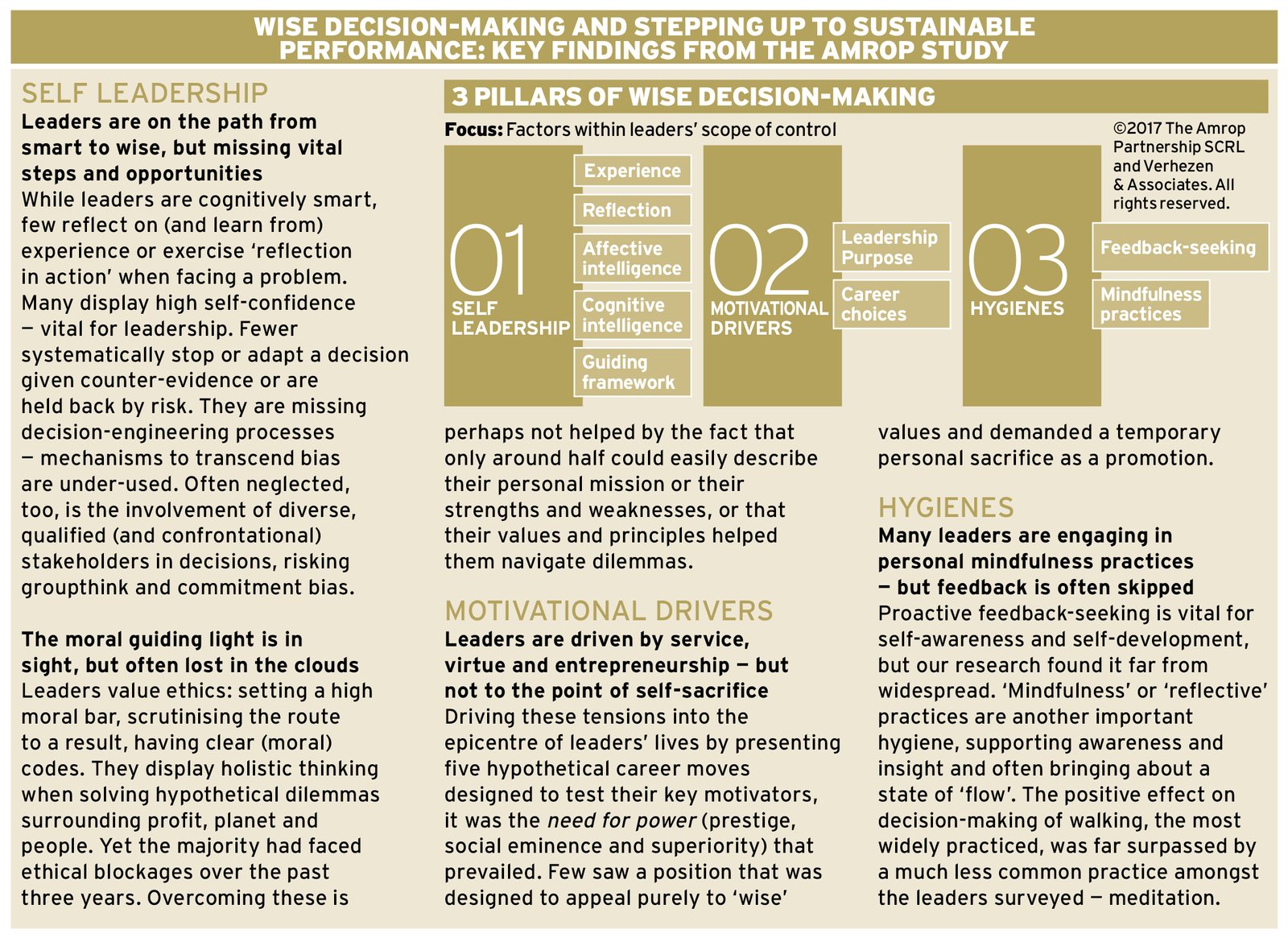

AW: Wise leadership translates into wise decision-making and Amrop has developed a model for this, working with Dr Peter Verhezen, a specialist in governance, ethical leadership and sustainability. We identified three pillars of wise decision-making

(see below): Self Leadership – how leaders exercise self-governance; Motivational Drivers – what drives leaders’ choices; and Hygienes – how leaders nourish their decision-making ‘health’.

An Amrop study conducted on the basis of the model found gaps between positive intentions and practice.[3] The concept clearly translates into questions about organisational purpose and, in turn, to core questions about evaluating the functionality of individual board members – and boards as a whole.

The starting point is to determine what kind of an organisation the board envisions. At what moral level should it operate? How important are non-financial objectives regarding sustainable performance? How should boards articulate a relevant business case and embed ESG, or even corporate citizenship criteria, in corporate reporting?

The following questions could be considered for ‘sustainable’ board evaluation. For example, it’s important to uncover not only strategic proactivity and responsiveness, but also the value that individual board members attribute to sustainability and ESG criteria. Do they consider these vital for a legitimate organisation, or as mere window dressing? Where are the zones of tension (or consensus?). Regarding specific indicators linked to wise decision-making, how exemplary are individual board members and the board as a whole? What measures reinforce ethical standards and protect these from short-term pressures? How are risk management and opportunism balanced? How does the board maintain its own feedback culture? What value is attributed to personal reflectiveness practices to maximise self-awareness? Finally, when recruiting board members, what criteria are in place to gauge their propensity to make wise decisions?

Incorporating such indicators into board evaluation can enable boards to identify areas of improvement or reinforcement in this critical area. Given the current fragile trust in leadership, it’s essential to determine remedial measures vis-à-vis external and internal stakeholders. Space also needs to be reserved on board agendas to address these specific issues. They are quite simply becoming critical to an organisation’s legitimacy to operate.

Footnotes:

1.Amel-Zadeh, A., Serafeim, G., (2017), Why and How Investors Use ESG Information: Evidence from a Global Survey, Said Business School, University of Oxford, Harvard Business School.

2.Klemash, S., Doyle, R., Smith., J.C., (2018), EY Center for Board Matters, Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation.

3.Between Q4 2016 and Q1 2017, 363 executives representing all regions of the world and major sectors completed a confidential Amrop survey. 94% held posts at C-suite level or above. 75% of their organisations had an international presence. Several items were drawn from previously validated research and are referenced in the full report.